INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGY

PART II

PERSONALITY

Учебно-методическое пособие для вузов

Издательско-полиграфический центр

Воронежского государственного университета

Утверждено научно-методическим советом факультета Романо-Германской Филологии 14 октября 2014 г., протокол № 2

Рецензент канд. филол. наук, доц. ВГУ Н.М. Шишкина

Учебно-методическое пособие подготовлено на кафедре английского языка гуманитарных факультетов факультета Романо – Германской Филологии Воронежского государственного университета.

Рекомендуется для студентов 1-2 курса Воронежского госуниверситета дневной формы обучения, обучающихся по следующим направлениям: психология, психолого-педагогическое образование.

Б1.Б.1 Иностранный язык (английский)

ПОЯСНИТЕЛЬНАЯ ЗАПИСКА

Учебно-методическое пособие «Introduction to Psychology Part II. Personality» предназначено для студентов первого и второго курса Воронежского госуниверситета дневной формы обучения, обучающихся по следующим направлениям: психология, психолого-педагогическое образование.

Целью данной работы является развитие у студентов необходимого уровня профессиональной коммуникативной компетенции для решения социально-коммуникативных задач в областях профессиональной и научной деятельности. Пособие также призвано обеспечить развитие информационной культуры, расширение кругозора и повышение общей культуры студентов, воспитание уважения к духовным ценностям разных стран и народов.

Пособие состоит из 3 разделов, вопросов для промежуточной аттестации и списка литературы. Для каждого раздела определены: тематика учебного общения, проблемы для обсуждения и типичные ситуации для всех видов устного и письменного речевого общения. В центре каждого раздела - текст, в ходе работы с которым отрабатываются рецептивные и продуктивные виды речевой деятельности. Тексты, являющиеся основой каждого раздела, аутентичны и актуальны для начального этапа профессионального общения. Пособие содержит большое разнообразие заданий, стимулирующих самостоятельную работу студентов.

В завершающую часть работы в рамках каждого урока входят пересказ основных положений текста, обсуждение ключевых моментов темы урока, написание эссе в рамках пройденной темы, поиск дополнительной информации по теме и ее презентация. Все упражнения рассчитаны на формирование умений и навыков, необходимых для осуществления различных видов речевой деятельности, а также на развитие письменной коммуникации.

На каждый раздел рекомендуется отводить 4 - 6 академических часов, хотя в зависимости от уровня подготовленности студентов программа может меняться.

Авторы надеются, что данное пособие будет соответствовать принципам коммуникативной направленности, культурной и педагогической целесообразности, интегративности и одновременно автономии студентов в процессе овладения иностранным языком, а также позволит студентам соответствовать уровню выпускных требований по дисциплине «Иностранный язык» с учетом специфики вуза и потребностей студентов.

Contents

1.Unit I.Explaining the Inner Life: Psychoanalytic Theories of Personality …5

2.Unit II. In Search of Personality: Trait, Learning, and Humanistic

Approaches …………………………………………………………………….16

3. Unit III. Assessing Personality ………………….………………………… 29

4. Credit questions...…………………………………………………………...38

5. References ….………………………………………………………………..40

Unit I

Explaining the Inner Life: Psychoanalytic Theories of Personality

Lead – in

1. Read the text and answer the questions:

a) Do you know people like Michelle leBlanc?

b) Is it common for individuals to show a certain set of characteristics in one situation and quite the opposite features in another one?

c) Do you know people whose behaviour is absolutely predictable?

d) What category might you include yourself in: predictable or unpredictable?

Prologue

When she went to a party - and she generally chose not to - Michelle LeBlanc could usually be found in the most inconspicuous corner. She rarely talked to more than a few close friends, if anyone at all, and her attempts at socializing consisted mostly of asking people to pass her something she couldn't reach from the bar. If they had taken the time to notice, people who observed her behavior at social engagements would probably have called her the shyest person they had ever seen.

Yet, if they had happened to see her in her job as hostess at a local restaurant, they would have been shocked: She was witty and charming, and customers were immediately drawn to her. It was as if she were an entirely different person.

And the same observers would have been even more surprised if they had seen her with her family, for here she was like still another person, so outgoing and energetic that her brothers always referred to her as the family social director. It was clear that her family adored her lively and outgoing ways, and that in their eyes she could do no wrong.

2. Read the following descriptions of two young men and try to comment on their personalities. Are they absolutely different?

Rick was without doubt the sloppiest person I had ever known. His dorm room was a mess. Clothes were strewn all over the place, some clean, some dirty—you never knew which, and of course, neither did he. There were piles of papers on his desk, and stacks of books cluttered the floor. If he had gone out of his way to be messy, he couldn’t have done a better job.

***

Ben was so neat and organized it almost drove me crazy. Everything was in its place, and if you picked up a book from its shelf and then put it down somewhere else, he immediately scooped it up and put it back where it belonged. Even his writing was extremely neat and controlled. I had the impression he would go into a panic if someone happened to spill something on the furniture.

At first glance, these sound like descriptions of people with very different personalities. Yet to one group of personality theorists, psychoanalysts, these two young men may actually be very similar - at least in terms of the underlying aspect of their personalities that is motivating their behavior. According psychoanalysts, behavior is caused largely by powerful forces that are shaped large degree by childhood experiences and about which people are unaware. The originator and most important of the theorists to hold such a view, indeed one of the best-known figures in all of psychology, is Sigmund Freud. An Austrian physician, Freud was the originator of psychoanalytic theory t the early 1900s.

Pre-reading

1. Look through Text A and find Russian equivalents for underlined words and expressions. Define to what part of speech they belong.

2. Match the following terms with their definitions:

| 1. Personality | a) Physicians or psychologists who specialize in psychoanalysis |

| 2. Psychoanalysts | b) Infantile wishes, desires, demands, and needs hidden from conscious awareness |

| 3. Psychoanalytic theory | c) The raw, unorganized, inherited part of personality whose purpose is to reduce tension created by biological drives and irrational impulses |

| 4. Unconscious | d) The principle by which the id operates, in which the person seeks the immediate reduction of tension and the maximization of satisfaction |

| 5. Instinctual drives | e)The part of personality that provides a buffer between the id and the outside world |

| 6. Id | f) The part of the superego that prevents us from doing what is morally wrong |

| 7. Pleasure principle | i) The part of personality that represents the morality of society as presented by parents, teachers, etc. |

| 8. Ego | j) The principle by which the ego operates, in which instinctual energy is restrained in order to maintain an individual’s safety and integration into society |

| 9. Reality principle | k) A part of the personality of which a person is unaware and which is a potential determinant of behavior |

| 10. Superego | l) The sum total of characteristics that differentiate people or the stability in a person’s behavior across different situations |

| 11. Conscience | m) Freud’s theory that unconscious forces act as determinants of personality |

| 13. Ego-ideal | n) The part of the superego that motivates us to do what is morally proper |

Text A

Part I

“Did you see the picture of Arnold Schwarzenegger sexing - oops, I mean, flexing - his muscles on the cover of People magazine this week?” asked Debbie, as she and her friend Kathy walked home from class.

Although this may seem to be merely an embarrassing slip of the tongue, according to psychoanalytic theory mistakes such as these are not errors at all. Rather, they are indications of deeply felt emotions and thoughts that are harbored in the unconscious, a part of the personality of which a person is not aware. Many of life’s experiences are painful, and the unconscious provides a “safe” haven for our recollections of such events, where they can remain without continually disturbing us. Similarly, the unconscious contains instinctual drives: infantile wishes, desires, demands, and needs that are hidden from conscious awareness because of the conflicts and pain they would cause us if they were part of our everyday lives.

To Freud, conscious experience is just the tip of the iceberg; just as with the unseen mass of a floating iceberg, the material found in the unconscious dwarfs the information about which we are aware. Much of people’s everyday behavior, then, is viewed as being motivated by unconscious forces about which they know little. For example, a child’s concern over being unable to please his strict and demanding parents may lead him to have low self-esteem as an adult, although he may never understand why his accomplishments - which may be considerable - never seem sufficient. Indeed, consciously he may recall his childhood with great pleasure; it is the unconscious, which holds the painful memories, that provokes the low self-evaluation.

According to Freud, to fully understand personality it is necessary to illuminate and expose what is in the unconscious. But because the unconscious disguises the meaning of material it holds, it cannot be observed directly. It is therefore necessary to interpret clues to the unconscious - slips of the tongue, fantasies, and dreams - in order to understand the unconscious processes directing behavior. A slip of the tongue, such as the one we quoted earlier, might be interpreted as revealing the speaker’s underlying unconscious sexual interests.

While the notion of an unconscious does not seem all that farfetched to most of us, this is only because Freudian theory has had such a widespread influence, with applications ranging from literature to religion. In Freud’s day, however, the idea of an unconscious was revolutionary, and the best minds of the time rejected his ideas as without basis and even laughable. That it is so easy for us to understand theories that are based on the assumption that there is a part of personality about which people are unaware - one that is responsible for much of our behavior - is a tribute to the influence of the theory.

***

Part II

To describe the structure of personality, Freud developed a comprehensive theory in which he said personality consisted of three separate but interacting parts, the id, the ego, and the superego. Although Freud describes these parts in very concrete terms, it is important to realize that they are not actual physical structures found in a certain part of the brain; instead, they represent parts of a general model of personality that describes the interaction of various processes and forces within one’s personality that motivate behavior. Yet the id, ego, and superego can be represented figuratively; as we can see in Figure 1, Freud suggested that they can be depicted as in the diagram, which also shows how the three components of personality are related to the conscious and the unconscious.

If personality were to consist only of primitive, instinctual cravings and longings, it would need only one component: the id. The id is the raw, unorganized, inherited part of personality whose sole purpose is to reduce tension created by primary drives related to hunger, sex, aggression, and irrational impulses. The id operates according to the pleasure principle, in which the goal is the immediate reduction of tension and the maximization of satisfaction.

Unfortunately for the id - but luckily for people and society - reality prevents the demands of the pleasure principle from being fulfilled in most cases. Instead, the world produces constraints: We cannot always eat when we are hungry, and sexual drives can be discharged only when time, place - and partner - are willing. To account for this fact of life, Freud suggested a second part of personality, which he called the ego.

The ego provides a buffer between the id and the realities of the objective, outside world. In contrast to the pleasure-seeking nature of the id, the ego operates according to the reality principle, in which instinctual energy is retrained in order to maintain the safety of the individual and help integrate the person into society. In a sense, then, the ego is the “executive” of personality: It makes decisions, controls actions, and allows thinking and problem solving of a higher order than the id is capable of. The ego is also the seat of higher cognitive abilities such as intelligence, thoughtfulness, reasoning, and lear ning.

The superego, the final personality structure to develop, represents the rights and wrongs of society as handed down by a person’s parents, teachers, and other important figures. It becomes a part of personality when children learn right from wrong, and continues to develop as people begin to incorporate the broad moral principles of the society in which they live into their own standards.

The superego actually has two parts, the conscience and the ego-ideal. The conscience prevents us from doing morally bad things, while the ego-ideal motivates us to do what is morally proper. The superego helps to control impulses coming from the id, making them less selfish and more virtuous.

Although on the surface the superego appears to be the opposite of the id, the superego and the id share an important feature: They are both unrealistic in that they do not consider the constraints of society. While this lack of reality within the superego pushes the person toward greater virtue, if left unchecked it would create perfectionists who were unable to make the compromises that life requires. Similarly, an unrestrained id would create a primitive, pleasure-seeking, thoughtless individual, seeking to fulfill without delay every desire. The ego, then, must compromise between the demands of the superego and the id, permitting a person to obtain some of the gratification sought by the id while keeping the moralistic superego from preventing the gratification.

Figure 1.

In Freud’s model of personality, there are three major structures: the id, the ego, and the superego. As the schematic shows, only a small portion of personality is conscious. It is important to note that this figure should not be thought of as an actual physical structure, but rather as a model of the interrelationships between the parts of personality.

Post – reading

1. Answer the following questions:

a) What does the unconscious provide for our recollections of painful events?

b) What can inability to please strict parents lead to?

c) Why cannot the unconscious be observed directly?

d) What can be considered the clues to the unconscious?

e) According what principles does id operate to?

f) What principle is instinctual energy restrained in?

g) What personality structure has two parts: the conscience and the ego-ideal?

h) What might an unrestrained id create?

2. Say if the statement is True or False. If the statement is False give the correct variant using the text.

a) To Freud, unconscious experience is the tip of the iceberg.

b) The painful memories of one’s childhood provoke the high self-evaluation.

c) A slip of the tongue might reveal the speaker’s underlying unconscious interests.

e) Personality consists of Three parts which interact with each other.

f) Reality can’t prevent the demands of the pleasure principle.

Pre-reading

1. Look through Text B and find Russian equivalents for underlined words and expressions. Define to what part of speech they belong.

2. Match the following terms with their definitions:

| 1. Anxiety | a. Behavior reminiscent of an earlier stage of development, carried out in order to have fewer demands put upon oneself |

| 2. Neurotic anxiety | b. A defense mechanism whereby people justify a negative situation in a way that protects their self-esteem |

| 3. Defense mechanisms | c. A refusal to accept or acknowledge anxiety-producing information |

| 4. Repression | d. A defense mechanism, considered healthy by Freud, in which a person diverts unwanted impulses into socially acceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviors |

| 5. Regression | e. Anxiety caused when irrational impulses from the id threaten to become uncontrollable |

| 6. Displacement | f. A phenomenon whereby adults have continuing feelings of weakness and insecurity |

| 7. Rationalization | g. Theorists who place greater emphasis than did Freud on the functions of the ego and its influence on our daily activities |

| 8. Denial | h. A concept developed by Jung proposing that we inherit certain personality characteristics from our ancestors and the human race as a whole |

| 9. Projection | i. According to Jung, universal symbolic representations of a particular person, object, or experience |

| Sublimation | j. The expression of an unwanted feeling or thought, directed toward a weaker person instead of a more powerful one |

| 10. Neo-Freudian psychoanalysts | k. The primary defense mechanism, in which unacceptable id impulses are pushed back into the unconscious |

| 11. Collective unconscious | l. Unconscious strategies people use to reduce anxiety by concealing its source from themselves and others |

| 12. Archetypes | m. A feeling of apprehension or tension |

| 13. Inferiority complex | n. A defense mechanism in which people attribute their own inadequacies or faults to someone else |

Text B

Part III

Freud’s efforts to describe and theorize about the underlying dynamics of personality and its development were motivated by very practical problems that his patients faced in dealing with anxiety, an intense, negative emotional experience. According to Freud, anxiety is a danger signal to the ego. Although anxiety may arise from realistic fears - such as seeing a poisonous snake about to strike - it may also occur in the form of neurotic anxiety, in which irrational impulses emanating from the id threaten to burst through and become uncontrollable. Because anxiety, naturally, is unpleasant, Freud suggested that people develop a range of defense mechanisms to deal with it. Defense mechanisms are unconscious strategies people use to reduce anxiety by concealing the source from themselves and others.

The primary defense mechanism is repression, in which unacceptable id impulses are pushed back into the unconscious. Repression is the most direct method of dealing with anxiety; instead of dealing with an anxiety-producing impulse on a conscious level, one simply ignores it. For example, a person who feels hatred for his father might repress these feelings: They would remain lodged within the id, since acknowledging them would be so anxiety - provoking. This does not mean, however, that they would have no effect: The true feelings might be revealed through dreams, slips of the tongue, or symbolically, in some other fashion. He might, for instance, have difficulty with authority figures, such as teachers, and do poorly in school. Alternatively, he might join the military, where he could give harsh orders to others and never have them questioned.

If repression is ineffective in keeping anxiety at bay, other defense mechanisms may be called upon. For example, regression might be used, whereby people behave as if they were at an earlier stage of development. By retreating to a younger age - for instance by complaining and throwing tantrums - they might succeed in having fewer demands put upon them.

Anyone who has ever been angered by a professor and then returned to the dorm and yelled at his or her roommate knows what displacement is all about. In displacement, the expression of an unwanted feeling or thought is redirected from a more threatening, powerful person to a weaker one. A classic case is yelling at one’s secretary after being criticized by the boss.

Rationalization, another defense mechanism, occurs when we distort reality by justifying what happens to us: We come up with explanations that allow us to protect our self-esteem. If you’ve ever heard someone saying that he didn’t mind being stood up for a date because he really had a lot of work to do that evening, you might be seeing rationalization at work.

In denial, a person simply refuses to accept or acknowledge an anxiety-producing piece of information. For example, when told that his wife has died in an automobile crash, a husband may at first deny the tragedy, saying that there must be some mistake, and only gradually come to conscious acceptance that she actually has been killed. In extreme cases, denial may linger; the husband may continue to expect that his wife will return home.

Projection is a means of protecting oneself by attributing unwanted impulses and feelings to someone else. For example, a man who feels sexually inadequate may complain to his wife that she is sexually inept.

Finally, one defense mechanism that Freud considered to be particularly healthy and socially acceptable is sublimation. In sublimation, people divert unwanted impulses into socially approved thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. For example, a person with strong feelings of aggression may become a butcher - and hack away at meat instead of people. Sublimation allows the butcher the opportunity not only to release the psychic tension, but to do so in a way that is socially acceptable.

All of us employ defense mechanisms to some degree according to Freudian theory. Yet some people use them so much that a large amount of psychic energy must be constantly directed toward hiding and rechanneling unacceptable impulses, making everyday living difficult. In this case, the result is a neurosis, a term which refer to mental disorders produced by anxiety.

***

Part IV

Freud’s personality theory presents an elaborate and complicated set of propositions - some of which are so removed from everyday explanations of behavior that they may appear difficult to accept. But laypersons are not the only ones to be concerned about the validity of Freud’s theory; personality psychologists, too, have been quick to criticize its inadequacies.

Among the most compelling criticisms is the lack of scientific data to support his theory. Although there are a wealth of individual assessments of particular people that seem to support the theory, there is a lack of definitive evidence showing that the personality is structured and operates along the lines Freud laid-out - due, in part, to the fact that Freud’s conception of personality is built on unobservable abstractions. Moreover, while we can readily employ Freudian theory in after-the-fact explanations, it is extremely difficult to predict how certain developmental difficulties will be displayed in the adult. For instance, if a person is fixated at the anal stage, he might, according to Freud, be unusually messy - or he might be unusually neat. His theory provides no guidance for predicting which manifestation of the difficulty will occur. Freudian theory produces good history, then, but not such good science. Finally, Freud made his observations - albeit insightful ones - and derived his theory from a limited population: primarily upper-class Austrian women living in the strict, puritanical era of the early 1900s. How far can one generalize beyond this population is a matter of considerable question.

Despite these criticisms, which cannot be dismissed, Freud’s theory has had an enormous impact on the field of psychology and indeed on all of western thinking. The concepts of the unconscious, anxiety, and defense mechanisms and the notion that adult psychological difficulties have their roots in childhood experiences have permeated people’s views of the world and their understanding of the causes of their own behavior and that of others. Moreover, psychoanalytic theory spawned a significant method of treating psychological disturbances. For these reasons, then, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory remains a significant contribution to our understanding of personality.

***

Part V

One particularly important outgrowth of Freud’s theorizing was the work done by a series of successors who were trained in traditional Freudian theory but: who later strayed from some of the major points of the original theory. These theorists are known as neo-Freudian psychoanalysts.

The neo-Freudians placed greater emphasis than did Freud on the functions of the ego, suggesting that it had more control than the id over day-to-day activities. They also paid greater attention to social factors and the effects of society and culture on personality development. Carl Jung, for example, who initially adhered closely to Freud’s thinking, later rejected the notion of the primary importance of unconscious sexual urges - a key notion of Freudian theory - and instead looked at the primitive urges of the unconscious more positively. He suggested that people had a collective unconscious, a set of influences we inherit from our own particular ancestors, the whole human race, and even animal ancestors from the distant past. This collective unconscious is shared by everyone, and is displayed by behavior that is common across diverse cultures, such as love of mother, belief in a supreme being, and even behavior as specific as fear of snakes.

Jung went on to propose that the collective unconscious contained archetypes, universal symbolic representations of a particular person, object, or experience, for instance, there is a mother archetype, which contains both our experiences with our own mothers and reflections of our ancestors’ relationship with mother figures. The existence of such an archetype is suggested by the prevalence of mothers in art, religion, literature, and mythology. (Think of the Virgin Mary, Earth Mother, wicked stepmothers of fairy tales, Mother’s Day, and so forth!) To Jung, these archetypes play an important role in determining our day-to-day reactions to stimuli. Jung might, for example, attribute the popularity of such movies as Star Wars to their use of broad archetypes of good and evil (the Force versus the Empire), father and son (Luke Sky walker versus Darth Vader), and several others.

To Alfred Adler, another important neo-Freudian psychoanalyst, Freudian theory’s emphasis on sexual needs was misplaced. Instead, Adler proposed that the primary motivation behind human behavior was a striving for superiority, an attempt to achieve perfection. Adler used the term inferiority complex to describe the phenomenon in which adults have not been able to overcome the feelings of inferiority that they had as children when they were physically small and limited in their knowledge about the world. Early social relationships with parents have an important effect on how well children are able to outgrow feelings of personal inferiority and instead orient themselves toward attaining more socially useful goals of perfecting society - rather than themselves.

Post – reading

1. Answer the following questions:

a) What is a danger signal to the ego?

b) What do defense mechanisms conceal?

c) How might true feelings be revealed?

d) Could you give an example of classic displacement?

e) Why may an aggressive person tend to become a butcher?

f) What is the main reason for such mental disorders as neurosis?

2. Say if the statement is True or False. If the statement is False give the correct variant using the text.

a) Freud theory is valid and has never been criticized.

b) It is always easy to predict developmental difficulties in the future life of the adult.

c) Freud derived his theory from a variety of population.

d) Neo-Freudians paid little attention to social factors and culture on personality development.

e) A collective unconscious is different across diverse cultures.

f) The existence of archetypes is reflected in religion, literature and mythology.

g) Alfred Adler believed that the primary motivation behind human behaviour is a striving for superiority.

Follow-up

1. Find the appropriate heading for each part of texts A and B:

a) Revising Freud: The Neo-Freudian Psychoanalysts.

b) Dealing with dangers from within: Defense Mechanisms.

c) Evaluating Freudian Theory.

e) Freud’s psychoanalytic Theory.

f) Structuring Personality: Id, Ego and Superego.

2. Say if the statement is True or False. If the statement is False give the correct variant using text A and B.

§ Psychoanalytic theory proposes that many deeply felt emotions and thoughts are not found in the unconscious, the part of personality of which a person is unaware. Personality is structured into two components: the ego, and the superego.

§ Defense mechanisms are unconscious strategies people use to reduce anxiety by concealing its source. Among the most important are repression, regression, displacement, rationalization, denial, projection, and sublimation.

§ Among the neo-Freudian psychoanalysts who built and modified psychoanalytic theory are Piaget, who developed the concepts of the collective unconscious and archetypes, and Leontyev, who coined the term “inferiority complex.”

3. The part of the personality of which we are unaware is the

a. oral stage b. conscience c. animus d. unconscious

4. Match each of the following with its description:

| a. | ____ Id | 1. | Diverting unwanted impulses into socially accepted behaviors |

| b. | ____ Ego | 2. | The personality’s decision maker |

| c. | ____ Superego | 3. | The distortion of reality to protect self-esteem |

| d. | ____ Sublimation | 4. | Feelings of inadequacy based on one’s life position |

| e. | ____ Archetypes | 5. | Attachment to some form of gratification |

| f. | ____ Inferiority complex | 6. | Unconscious cravings for pleasure |

| g… | ____ Rationalization | 7. | Universal symbolic representations of people, objects, or experiences |

| h. | ____ Fixation | 8. | The component of the personality responsible for moral behavior |

5. Theresa, still reeling from an argument with her husband, yells at her young son when he accidentally spills his juice, and sends him to his room. The defense mechanism employed by Theresa is called

a. repression b. regression c. displacement d. projection

6. An intense, negative emotional experience that serves as a danger signal to the ego is ____________.

7. The idea of a collective unconscious was suggested by Alfred Adler. True or false?

8. Who of the following theorists suggested that our primary motivation is a striving for superiority?

a. Freud b. Allport c. Jung d. Adler

9. Use Psychoanalytic theory to comment on the following expression: What You See Is Not What You Get. Find information from texts A and B to support your ideas. You can use media sources as well. Then write down an opinion essay (250 words).

10. Project work. Use different media sources to find out more information about Psychoanalytic theory of personality and its theorists. Make up a good presentation in class.

Unit II

In Search of Personality: Trait, Learning, and Humanistic Approaches

Lead-in

1. Which of the following adjectives are positive and which are negative?

funny, unreliable, self-confident, caring, imaginative, outgoing, helpful, rude, easy-going, stubborn, cooperative, selfish, shy, disorganized, forgetful, active, lazy, loyal, arrogant, polite, responsible, decisive, bossy, energetic, ambitious, determined, careful, reserved, mean, generous, intelligent, sensitive

| Positive | funny, ………. |

| Negative | unreliable, ………… |

2. Analyze the conversation printed below.

a. How many people are discussed?

b. What is characterized?

c. Are personality traits consistent across different situations?

“Tell me about Roger, Sue,” said Wendy.

“Oh, he’s just terrific. He’s the friendliest guy I know - goes out of his way to be nice to everyone. He hardly ever gets mad. He’s just so even-tempered no matter what’s happening. And he’s really smart, too. About the only thing I don’t like is that he’s always in such a hurry to get things done; he seems to have boundless energy, much more than I have.”

“He sounds great to me, especially in comparison to Richard,” replied Wendy. “He is so self-centered and arrogant it drives me crazy. I sometimes wonder why I ever started going out with him.”

Friendly. Even-tempered. Smart. Energetic. Self-centered. Arrogant.

If we were to analyze the conversation printed above, the first thing we would notice is that it is made up of a series of trait characterizations of the two people being discussed. In fact, most of our understanding of the reasons behind others’ behavior is based on the premise that people possess certain traits that are assumed to be consistent across different situations. A number of formal theories of personality employ variants of this approach. We turn now to a discussion of these and other personality theories, all of which provide alternatives to the psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious processes in determining behavior.

Pre-reading

1.Look through Text C and find Russian equivalents to the underlined words and expressions.

2. Match the following terms with their definitions:

| 1. Traits | a. A single personality trait that directs most of a person's activities (e.g., greed, lust, kindness) |

| 2. Trait theory | b. Less important personality traits (e.g., preferences for certain clothes or movies) that do not affect behavior as much as central and cardinal traits do |

| 3. Cardinal trait | c. A statistical technique for combining traits into broader, more general patterns of consistency |

| 4. Central traits | d. According to Cattell, clusters of a person’s related behaviors that can be observed in a given situation |

| 5. Secondary traits | e. The sixteen basic dimensions of personality that Cattell identified as the root of all behavior |

| 6. Factor analysis | f. A state of self-fulfillment in which people realize their highest potential |

| 7. Surface traits | g. Enduring dimensions of personality characteristics differentiating people from one another |

| 8. Source traits | h. A set of major characteristics that make up the core of a person's personality |

| 9. Introversion-extroversion | i. The impression one holds of oneself |

| 10. Neuroticism-stability | j. A model that seeks to identify the basic traits necessary to describe personality |

| 11. Learned not-thinking | k. Learning that is the result of viewing the actions of others and observing the consequences |

| 12.Social learning theory (of personality) | l. The theory that emphasizes people’s basic goodness and their natural tendency to rise to higher levels of functioning |

| 13. Observational learning | m. Eysenck’s personality spectrum encompassing people from the moodiest to the most even-tempered |

| 14. Determinism | n. The theory that suggests that personality develops through observational learning |

| 15. Humanistic theory (of personality) | o. Dollard and Miller’s notion that unpleasant thoughts can be repressed, eliminating negative feelings that are otherwise present |

| 16. Self-concept | p. According to Eysenck, a dimension of personality traits encompassing the shyest to the most sociable people |

| 17. Unconditional positive regard | q. The view that suggests that behavior is shaped primarily by factors external to the person |

| 18. Self-actualization | r. Supportive behavior from another individual, regardless of one's words or actions |

3. Scan the text and suggest appropriate headings for each part (I – X):

- Factoring out Personality.

- Which Theorist’s Traits are the Right Traits?: Evaluating Trait Theories of Personality.

- Labeling Personality: Trait Theories.

- Getting Down to Basics: Allport’s Trait Theory.

- Understanding the Self.

- Explaining the Outer Life, Ignoring the Inner Life.

- Where Freud Meets Skinner.

- Evaluating Learning Theories of Personality.

- Where the Inner Person Meets the Outer One.

- Answering the right question: Which theory is Right.

Text C

Part I

If someone were to ask you to characterize another person, it is probable that you - like the two people in the conversation just presented - would come up with a list of their personal qualities, as you see them. But how would you know which of these qualities were most important in determining that person’s behavior?

Personality psychologists have asked similar questions themselves. In order to answer them, they have developed a sophisticated model of personality known as trait theory. Traits are relatively enduring dimensions of personality characteristics along which people differ from one another.

Trait theorists do not assume that some people have a trait and others do not; rather, they propose that all people have certain traits, but that the degree to which the trait applies to a specific person varies and can be quantified. For instance, you might be relatively friendly, while I might be relatively unfriendly.

But we both have a “friendliness” trait, although you would be quantified with a higher score and I with a lower one. By taking this approach, the major challenge for trait theorists has been to identify the specific primary traits necessary to describe personality - and, as we shall see, different theorists have come up with surprisingly different sets.

***

Part II

When Gordon Allport sat down with an unabridged dictionary in the 1930s, he found some 18,000 separate terms that could be used to describe personality. But which of these were the most crucial?

Allport answered this question by suggesting that there were three basic categories of traits: cardinal, central, and secondary (Allport, 1961, 1966). A cardinal trait is a single characteristic that directs most of a person’s activities. For instance, a Don Juan is motivated to seduce every woman he meets; another person might be totally driven by power needs. Most people, however, do not develop all-encompassing cardinal traits; instead, they possess a handful of central traits that make up the core of personality. Central traits, such as honest) or sociability, are the major characteristics of the individual; they usually number from five to ten in any one person. Finally, secondary traits are characteristics that affect behavior in fewer situations and are less influential than central or cardinal traits. For instance, a preference for ice cream or a dislike of modern art would be considered a secondary trait.

***

Part III

More recent attempts at discovering the primary traits have centered on a statistical technique known as factor analysis. Factor analysis is a method for combining descriptions of many different individual traits into broad, overall patterns of consistency.

Raymond Cattell (1965) suggested that the characteristics that can be observed in a given situation represent surface traits, clusters of related behaviors such as assertiveness or gregariousness. Yet these surface traits are merely representations of more fundamental source traits. Source traits are the sixteen basic dimensions of personality that Cattell identified as being at the root of all behavior. These traits are described in Table 1.

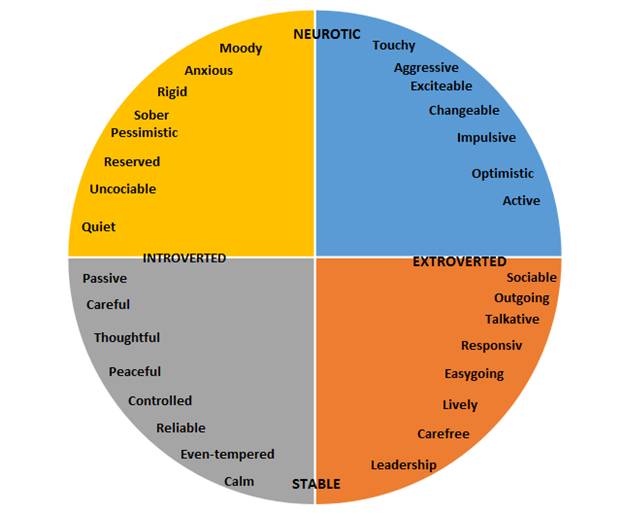

Although he also used the method of factor analysis to identify patterns within traits, Hans Eysenck (1975), another trait theorist, came to a very different conclusion about the nature of personality. He found that personality could be best described in terms of two basic dimensions: introversion-extroversion and neuroticism-stability. On the one extreme of the introversion-extroversion dimension are people who are quiet,careful, thoughtful, and restrained (the introverts), and on the other are those who are outgoing, sociable, and active (the extroverts). Independently of that, people can be rated as neurotic (moody, touchy, sensitive) or stable (calm, reliable, even-tempered); see Figure 2. By evaluating people along these two dimensions, Eysenck has been able to make accurate predictions of behavior in a number of situations.

Table 1. The sixteen trait dimensions in Cattell’s trait theory of personality

| Low Scores | High Scores | ||

| Sizia: reserved, detached, aloof | Affecta: outgoing, warmhearted | ||

| Low intelligence: dull | High intelligence: bright | ||

| Low ego strength: agitated, emotionally, unstable | High ego strength: calm, emotionally stable | ||

| Submissiveness: humble, docile | Dominance: assertive, competitive | ||

| Desurgency: sober, serious | Surgency: happy-go-lucky, fun-loving | ||

| Weak superego: ignores rules, immoral | Strong superego: conscientious, moral | ||

| Threctia: shy, timid | Parmia: adventurous, bold | ||

| Harria: tough-minded, self-reliant | Premsia: tender-minded, sensitive | ||

| Alaxia: trusting, accepting | Protension: suspicious, rejecting | ||

| Praxernia: practical, down-to-earth | Autia: imaginative, head-in-the-clouds | ||

| Artlessness: forthright, socially awkward | Shrewdness: astute, socially skilled | ||

| Untroubled adequacy: secure, self- assured | Guilt proneness: apprehensive, self-blaming | ||

| Conservatism: conservative, traditional | Radicalism: liberal, free-thinking | ||

| Group adherence: joins groups, follows others | Self-sufficiency: independent, self-reliant | ||

| Low self-sentiment integration: uncontrolled, impulsive | High self-sentiment integration: controlled, compulsive | ||

| Low ergic tension: relaxed, composed | High ergic tension: tense, frustrated | ||

Figure 2.

***

Part IV

We have seen that trait theorists describing personality have come to quite different conclusions about which traits are the most fundamental and descriptive. The difficulty in determining which of the theories is most accurate has led many psychologists to question the validity of trait conceptions of personality in general.

Actually, there is an even more fundamental difficulty with trait approaches. Even if we are able to identify a set of primary traits, we are left with little more than a label or description of personality - rather than an explanation of behavior. If we say that someone donates money to charity because he or she has the trait of “generosity,” we still do not know why the person became generous in the first place, or the reasons for generosity being displayed in a given situation. Traits, then, provide nothing in the way of explanation of behavior, but are merely descriptive labels.

Perhaps the biggest problem with trait conceptions is one that is fundamental to the entire area of personality: Is behavior really as consistent over different situations as trait conceptions would imply?

***

Part V

While psychoanalytic and trait theories concentrate on the inner person - the stormy fury of an unobservable but powerful id or a hypothetical but critical set of traits - learning theories of personality focus on the outer person. In fact, to a strict learning theorist, personality is simply the sum of learned responses to the external environment.Internal events such as thoughts, feelings, and motivations are ignored; while their existence is not denied, learning theorists say that personality is best understood by looking at features of a person’s environment.

According to the most influential of the learning theorists, B. F. Skinner, personality is a collection of learned behavior patterns (Skinner, 1975). Similarities in responses across different situations are caused by similar patterns of reinforcement that have been received in such situations in the past. If I am sociable both at parties and at meetings, then, it is because I have been reinforced previously for displaying social behaviors - not because I am fulfilling some unconscious wish based on experiences during my childhood or because I have an internal trait of sociability.

Strict learning theorists such as Skinner are less interested in the consistencies in behavior across situations, however, than in ways of modifying behavior. In fact, their view is that humans are infinitely changeable; if one is able to control and modify the patterns of reinforced in a situation, behavior that other theorists would view as stable and unyielding can be changed, and ultimately improved. These learning theorists, then, are optimistic in their attitudes about the potential for resolving personal and societal problems through treatment strategies based on learning theory - methods.

***

Part VI

Not all learning theories of personality take such a strict view in rejecting the importance of what is “inside” the person by focusing solely on the “outside.” John Dollard and Neal Miller (1950) are two theorists who tried to meld psychoanalytic notions with traditional stimulus-response learning theory in an ambitious and influential explanation of personality.

Dollard and Miller translated Freud’s notion of the pleasure principle - trying to maximize one’s pleasure and minimize one’s pain - into terms more suitable for learning theory by suggesting that both biological and learned drives energize an organism. If the consequence of a particular behavior is a reduction in drive, the drive reduction is viewed as reinforcing, which in turn increases the probability of the behavior occurring again in the future.

According to Dollard and Miller, the Freudian notion of repression, in which anxiety-producing thoughts are pushed into the unconscious, can be looked at instead as an example of learned not-thinking. Suppose the thought of sexual intercourse makes you anxious. Freud might propose that you would deal with the anxiety by avoiding conscious thought about intercourse and instead relegating the idea to your unconscious - i.e., repressing the thought. In contrast, Dollard and Miller might suggest that “not thinking” about the topic will become reinforcing to you because you find that it leads to a reduction in the unpleasant state of anxiety that thinking about it evokes. “Not thinking,” then, will become an increasingly likely behavior.

***

Part VII

Unlike other learning theories of personality, social learning theory emphasizes the influence of a person’s thoughts, feelings, expectations, and values in determining personality. According to Albert Bandura, the main proponent of this point of view, we are able to foresee the possible outcomes of certain behaviors in a given setting without actually having to carry them out. This takes place mainly through the mechanism of observational learning - viewing the actions of others and observing the consequences (Bandura, 1977).

More so than other learning theories, social learning theory considers how we can modify our own personalities through the exercise of self-reinforcement. We are constantly judging our own behavior based on our internal expectations and standards, and then providing ourselves with cognitive rewards or punishments. For instance, a person who cheats on her income tax may mentally punish herself, feeling guilty and displeased with herself. If, just before mailing her tax return, she corrects her “mistake,” the positive feelings she will experience will be rewarding and will serve to reinforce her view of herself as a law-abiding citizen.

***

Part VIII

By ignoring the internal processes that are uniquely human, traditional learning theorists such as Skinner have been accused of oversimplifying personality so much that the concept becomes meaningless. In fact, reducing behavior to a series of stimuli and responses and excluding thoughts and feelings from the realm of personality leaves learning theorists practicing an unrealistic and inadequate form of science, at least in the eyes of their critics.

Of course, some of these criticisms are blunted by social learning theory, which explicitly considers the role of cognitive processes in personality. Still, all learning theories share a highly deterministic view of human behavior, a view that maintains behavior is shaped primarily by external forces. In the eyes of some critics, determinism disregards the ability of people to take control of their behavior.

On the other hand, learning approaches have had a major impact in a variety of ways. For one thing, they have helped make the study of personality an objective, scientific venture by focusing on observable features of people and the environments in which they live. Beyond this, learning theories have produced important, successfulmeans of treating personality disorders. The degree of success these treatments have enjoyed provides confidence that learning theory approaches have merit.

***

Part IX

Where, in all these theories of personality, is an explanation for the saintliness of a Mother Teresa, the creativity of a Michelangelo, the brilliance and perseverance of an Einstein? An understanding of such unique individuals - as well as more everyday sorts of people who share some of the same attributes - comes from humanistic theory.

According to humanistic theorists, the theories of personality that we have discussed share a fundamental error in their views of human nature. Instead of seeing people as controlled by unconscious, unseen forces (as does psychoanalytic theory), a set of stable traits (trait theory), or situational reinforcements and punishments (learning theory), humanistic theory emphasizes people’s basic goodness and their tendency to grow to higher levels of functioning. It is this conscious, self-motivated ability to change and improve, along with people’s unique creative impulses, that make up the core of personality.

The major representative of the humanistic point of view is Carl Rogers (1971). Rogers suggests that there is a need for positive regard which reflects a universal requirement to be loved and respected. Because others provide this positive regard, we grow dependent on them. We begin to see and judge ourselves through the eyes of other people, relying on their values.

According to Rogers, one outgrowth of placing import on the values of others is that there is often some degree of mismatch between a person’s experiences and his or her self-concept, or self-impression. If the mismatch is minor, so are the consequences. But if it is great, it will lead to psychological disturbances in daily functioning, such as the experience of frequent anxiety.

Rogers suggests that one way of overcoming the discrepancy between experience and self-concept is through the receipt of unconditional positive regard from others - a friend, a spouse, or a therapist. Unconditional positive regard consists of supportive behavior on the part of an observer, no matter what a person says or does. This support, says Rogers, allows people the opportunity to evolve and grow both cognitively and emotionally as they are able to develop more realistic self-concepts.

To Rogers and other humanistic personality theorists (such as Abraham Maslow), an ultimategoal of personality growth is self-actualization. Self-actualization is a state of self-fulfillment in which people realize their highest potential: This, Rogers would argue, occurs when their experience with the world and their self-concept are closely matched. People who are self-actualized accept themselves as they are in reality, which enables them to achieve happiness and fulfillment.

Although humanistic theories suggest the value of providing unconditional positive regard toward people, unconditional: positive regard toward humanistic theories has been less forthcoming from many personality theorists. The criticisms have centered on the difficulty of verifying the basic assumptions of the theory, as well as on the question of whether unconditional positive regard does, in fact, lead to greater personality adjustment.

Humanistic approaches have also been criticized for making the assumption that people are basically “good” - a notio