Dare to read: Нэнси Дрю и Братья Харди

(https://vk.com/daretoreadndrus)

ПРИЯТНОГО ЧТЕНИЯ!

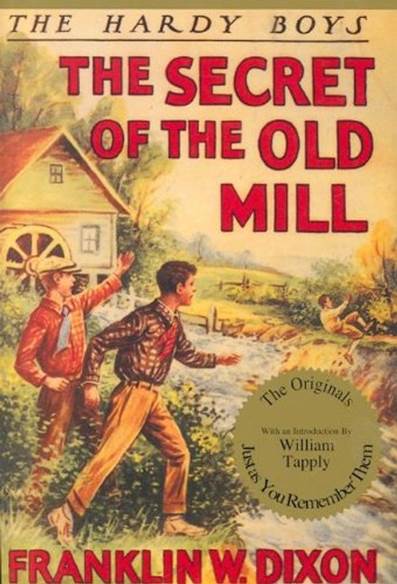

Franklin W. Dixon

Hardy Boys Mystery Stories: Volume Three

The Secret of the Old Mill

Copyright by Simon & Schuster, Inc

Published by Grosset & Dunlap, Inc

This is original text, 1927

The Hardy Boys break up a counterfeiting ring centered at an old mill on the outskirts of Bayport.

CHAPTER I

A Five Dollar Bill

The afternoon express from the north steamed into the Bayport station to the usual accompanying uproar of clanging bells from the lunch room, shouting redcaps, and a bellowing train announcer.

Among the jostling, hurrying crowd on the platform were two pleasant-featured youths who scanned the passing coaches expectantly.

"I don't see him," said Frank Hardy, the older of the pair, as he watched the passengers descending from one of the Pullman coaches.

"Perhaps he stopped at some other town and intends coming in on the local. It's only an hour later," suggested his brother Joe.

The boys waited. They had met the train expecting to greet their father, Fenton Hardy, the nationally famous detective, who had been away from home for the past two weeks on a murder case in New York. It appeared that they were to be disappointed. When the last of the Bayport passengers had left the train Fenton Hardy was not among them.

"We'll come back and meet the local," said Frank at last.

The brothers were about to turn away and retrace their steps down the platform when they saw a tall, well-dressed stranger swing himself down from the steps of the nearest coach. He was a man of about thirty, dark and clean-shaven, and he hastened over toward them.

"I want to pay a fellow a dollar out of this five," remarked the stranger, as he came up to the boys. "Can you change the bill?"

At the same time he produced a five dollar bill from his pocket and held it out inquiringly.

He was a pleasant-spoken young man and he was evidently in a hurry.

"I could try the lunch room, I suppose, but there's such a crowd that I'll have trouble being waited on," he explained, the bill fluttering in his hands.

Frank looked at his brother and began feeling in his pockets.

"I've got three dollars, Joe. How about you?"

Joe dug up the loose change in his possession. There was a dollar bill, a fifty-cent piece, and three quarters.

''Two dollars and a quarter," he announced, '"I guess we can make it."

He handed over two dollars to Frank, who added it to the three dollars of his own and gave the money to the stranger, who gave Frank the five dollar bill in exchange.

"Thanks, ever so much," said the young man. "You've saved me a lot of trouble. My friend is getting off at this station and I wanted to give him the dollar before he left. Thanks."

"Don't mention it," replied Frank carelessly, putting the bill in his pocket. "We'll get it changed between us."

The young man nodded, smiled at them and hastened back up the steps of the coach, with a carefree wave of his hand.

"I'm glad we were able to help him out," observed Joe. "It was just by chance that I had that small change too. Mother gave me some money to buy some pie-plates."

"Pie-plates!" exclaimed Frank, with a grin, "There's nothing I'd rather see coming into the house than more pie-plates. More pie-plates mean more pie."

"We might as well go down and get now, before I forget. There's a shop the street and we can get the plates and this five dollar bill changed. It'll help kill time before the local comes in."

The two lads went down the platform, out through the station to the main street of Bayport, basking in the summer sunlight. They were healthy, normal American boys of high school age. Frank, being a year older than his brother, was slightly taller. He was slim and dark, while his brother was somewhat stouter of build, with fair, curly hair. As they strolled down the street they received and returned many greetings, for both boys were well-known and popular in Bayport.

Before they reached the store they heard the shriek of the whistle and the clanging of the bell that indicated that the express was resuming its southward journey.

"Our friend can travel in peace," remarked frank. "He got his five changed anyway."

"And the other fellow got his dollar. Everybody's happy."

They reached the store and paused outside the entrance to examine an assortment of baseball bats, discussing the relative merits and weights of each, then poked around in a tray of mitts, trying them on and agreeing that none equaled the worn and battered mitts they had at home. Finally they entered the shop, where they were greeted by the proprietor, a chubby and genial man named Moss. Mr. Moss was sitting on the counter reading a newspaper for business was dull that afternoon, but he cast the sheet aside when they came in.

"Looking for clues?" he asked humorously, as they came in.

As sons of Fenton Hardy, and as amateur detectives of some ability in their own right, the boys were frequently the butt of jesting remarks concerning their hobby, but they invariably took them in the spirit of good-natured raillery in which they were meant.

"No clues here," continued Mr. Moss, "You won't find a single, solitary clue in the place. I had a crate of awfully nice bank robbery clues in yesterday, but they've all been snapped up. I expect some nice murder clues in to-morrow morning, if you'd care to wait that long. Or perhaps you'd like me to order you a few kidnapping clues. Size eight and a half, guaranteed not to wear, tear or tarnish."

Mr. Moss rattled on, with an air of great gravity, burst into a roar of laughter at his own joke, then swung his feet against the side of the counter.

"Well, boys, what'll it be?" he asked, rubbing his eyes, as the two brothers grinned aft him. "What can I do for you?"

"We want some pie-plates," said Joe "Three."

"Small ones, I suppose," said Mr. Moss then chuckled hugely as the hoys looked at him in indignation.

"I should say not," returned Frank. "The biggest you've got."

Mr. Moss laughed very much at this also; and swung himself down from the counter and went in search of the pie-plates. He returned eventually with three that seemed to be of the required size and quality.

"Wrap 'em up," said Frank, throwing the five dollar hill on the counter.

Mr. Moss wrapped up the plates, then picked up the hill and went over to the cash register. He rang up the amount of the salt and was about to put the money in the till when lie suddenly hesitated, then held the bill up to the light. Slowly, he came back to the counters, rubbing the bill between thumb and forefinger, feeling its texture and minutely examining the surface.

"Where did you get this hill, hoys?" he asked seriously.

"We just changed it for a stranger on the train." answered Frank. "What's the matter with it?"

"Looks bad to me," replied Mr. Moss dubiously. "I'm afraid I can't take a chance on it."

He handed the bill back to Frank, then indicated the package on the counter.

"What are you going to do about the plates?" he asked. "Have you any money besides that bill?"

"Not a nickel," said Joe. "At least, not enough to pay for the plates. But do you really think the bill is no good?"

"I've handled a lot of them. It doesn't look good to me. I tell you what you'd better do, Take it over to the bank across the street and ask the cashier what he thinks of it."

The boys looked at one another in dismay. It had never occurred to them that there might be anything wrong with the money. Now it dawned on them that there had been something suspicious about the affable stranger's request. Had they really been victimized?

"We'll do that," agreed Frank. "Come on, Joe. Keep those plates for us, Mr. Moss. If the bill is bad we'll be back with some real money later on."

They crossed the street to the bank and went up to the cashier's cage. They knew the cashier well and he smiled at them as Frank pushed the five dollar bill under the grating.

"Want it changed?" he asked.

"We want to know if it's good, first."

The cashier, a sharp-featured, elderly man with spectacles, then took a sharp glance at the bill. He pursed up his lips as he felt the texture of the paper. Then he flicked the bill across to them again.

''Sorry," he said." You've been stung, boys. It's counterfeit."

"Counterfeit!" exclaimed Frank.

"You aren't the first one who has been fooled. There's been a lot of counterfeit money going around the past few days. It's very cleverly done and it's apt to fool any one who isn't used to handling a lot of bills. Where did you get it?"

"A fellow got off the train and asked us to change it for him."

The cashier nodded.

"And by now he is miles away, probably getting ready to work the same trick at the next station. I guess you'll have to pocket your loss, boys. It's tough luck."

CHAPTER II

Counterfeit Money

The Hardy boys left the bank, feeling at once foolish and wrathful.

"Stung!" declared Frank. "Stung by a counterfeit bill! Oh, if the fellows hear of this we'll never hear the end of it!"

"What a fine pair of greenhorns we must have looked to that slick stranger! I'd like to lay my hands on him for about five seconds. I'll bet he's been laughing to himself ever since about how easily we were fooled."

"I'll say we were easy. We hadn't a suspicion in the world."

"After all," Joe remarked, "that bill might have fooled any one. You can't deny that it looks mighty like a real five."

They halted on the corner and again examined the money. Only an experienced eye could have detected any difference between the counterfeit bill and a genuine one. It was crisp and new and appeared in every respect identical with any bona fide five dollar bill that had ever been legitimately issued by the Federal Government.

"If we were dishonest we could palm this off on almost any one, just as we had it palmed off on us," said Joe. "Oh, well – live and learn. I hate to think of that fellow laughing at us, though. It's a nice price to pay for a lesson not to be too trustful of strangers after this."

"It cost me more than it cost you," Frank pointed out. "It was just my luck that I had three dollars on me and you had only two."

This phase of the matter had not occurred to Joe before, so he felt considerably more cheerful in the thought that he had not, after all, been the chief loser.

They went back to the store and dolefully reported to Mr. Moss that he had been right in his surmise about the bill.

"It was bad, all right," Frank told him. "The cashier took one look at it, and that was enough."

Mr. Moss nodded sympathetically.

"Well, it's too bad you were stung," he said. "But I'd rather it was you than me. In business, we have to be careful. As a matter of fact, I think it would have fooled me, only the bank warned me this morning that there was some counterfeit money going around and that I'd batter be on my guard against any new bills. The minute I saw your five was fresh and new I got suspicious. It's certainly a clever imitation. Whoever is putting the stuff out is a real artist at that game."

"We'll be back for the pie-plates later," promised Joe. "But we didn't want you to think we were trying to pass bad money on you."

Mr. Moss laughed at the idea.

"The Hardy boys pass counterfeit money!" he exclaimed. "I know you better than that, I hope. I'll keep the plates for you, or you can take them now and bring back the money later. Good money, though," he added, wagging his finger at them.

"We'll be back," they told him.

They went toward the station to wait for the local train on which they expected their father to arrive, and while they waited, sitting on a platform bench, they gloomily discussed the imposition of which they had been the victims.

"It isn't so much losing my three dollars," declared Frank. "It's the thought of being fooled by such a simple trick. We should have known that the fellow had plenty of time to get his money changed at the lunch counter or at the cigar stand, or even the ticket office. Instead of that we dug into our pockets like lambs –"

"Lambs don't have pockets," Joe pointed out.

"All the better for them. They're so innocent they'd be fleeced of everything they put in 'em, anyway. Just like us. We handed over all our money to a total stranger and let him give us a bad bill that we didn't even take the trouble to look at. I wish somebody would kick me all around the block."

While the Hardy boys are sitting on the bench, gloomily awaiting the arrival of their father and preparing to tell him of how they had been fooled by the stranger, it will not be out of place to introduce them still further to the readers of this volume.

As related in the first volume of this series, "The Hardy Boys: The Tower Treasure," Frank and Joe Hardy were the sons of Fenton Hardy, a private detective of international fame. Mr. Hardy, who had been for many years on the New York police force and who had later resigned to carry on a private detective practice, was a criminologist of note. He knew by sight and by reputation most of the notorious criminals of his day, and his mastery over all the branches of his profession was such as to place him at the very forefront of American detectives. So great had been the demand for his services in solving the mysteries of crimes that had baffled the detective forces of other cities that he had found it much more lucrative to carry on a practice of his own than to remain attached to the service in any one city, even such a city as the great American metropolis.

Fenton Hardy, with his wife, Laura Hardy, and their two sons, Frank and Joe, had accordingly moved to Bayport, a city of about fifty thousand inhabitants, situated on Barmet Bay, on the Atlantic Ocean. There Frank and Joe had gone to school until now they were in the Bayport high school. Both boys were fully conscious of the fame of their father and were eager to follow in his footsteps, although their mother had expressed a desire that they fit themselves for some less hazardous and more conventional profession.

However, the Hardy boys had inherited much of their father's ability and deductive talent. Already they had aided in solving two mysteries that had kept Bayport by the ears. As related in "The Hardy Boys: The Tower Treasure," they had solved the mystery of the theft of valuable jewels and bonds from Tower Mansion, after even Fenton Hardy himself had been unable to discover where the thief had hidden the loot. In the second volume of the series, "The Hardy Boys: The House on the Cliff," has been told how the Hardy boys discovered the haunt of a gang of smugglers who were operating in Barmet Bay. In this case they had received a substantial reward, as Federal agents had tried in vain to locate the smugglers' base of activities for many months.

Following the adventures at the house on the cliff an uneventful winter and spring had passed, the brothers devoting themselves to their studies and to an occasional winter holiday. Christmas had come with many presents, and now warm weather was once more at hand.

Because of the pride they took in their achievements as amateur detectives, the Hardy boys felt very keenly the ignominy of being so easily fooled by the stranger who had passed the counterfeit money upon them.

"Dad will have the laugh on us now," muttered Joe, as they heard the distant whistle of the approaching train.

"Well, we'll tell him about it, anyway. Who knows but what a big case might arise out of this?"

The afternoon local pulled into the station and Fenton Hardy stepped down from the parlor car, bag in hand, light coat over one arm. He was a tall, dark-haired man of about forty years of age. He had a quick, pleasant smile for his sons and he shook hands with them warmly.

"How's mother?" he asked, after the first greetings.

"She's fine," replied Frank. "She said there'd be something special for supper to-night, seeing you're back."

"Good! And what have you two been doing? Kept out of mischief, I hope."

"Well, we've kept out of mischief," said Joe; "but we haven't kept out of trouble."

"What's the matter?"

"We just got fooled by a smart stranger who stepped off the express. It cost us five dollars."

"How did that happen?"

"He asked us to change a five dollar bill for him –"

"Ah, ha!" exclaimed Fenton Hardy, raising his eyebrows. "And what then?"

"It was counterfeit."

Mr. Hardy looked grave.

"Have you got it with you?"

"Yes," answered Frank, producing the bill. "I don't think we can be blamed such an awful lot for being fooled. It certainly looks mighty like a good one."

Fenton Hardy put down his bag and examined the bill closely for a moment. Then he folded it up and put it in his waistcoat pocket.

"I'll take care of this, if you don't mind," he said, picking up his bag and beginning to walk toward the station exit. "As it happens, I know something about this money."

"What do you mean, dad?" asked Frank quickly.

"I don't mean that I know anything about this particular five dollar bill, but I know something about this counterfeit money in general. As a matter of fact, that is why this trip took me longer than I had thought it would. "When I finished the case that originally took me away, the Government called me in on this counterfeit money case."

"Is there a lot of it going around?"

"Too much. Within the past few weeks the East has been flooded with it, and the circulation seems to be spreading. There seems to be a central counterfeiting plant somewhere, with experts in charge of it, and they are turning out imitation bills so clever that the average person can hardly detect them. The Federal authorities are worrying a great deal about it."

"And this is one of the bills?"

"It looks just like some of the others that have been turned in, although chiefly they have been dealing in tens and twenties. The man who stepped off the train was probably one of their agents, trying to convert as much of the counterfeit money into good cash as he could. When he saw that you were only boys he thought there would be a better chance of getting change for five dollars than ten. Then, of course, he may only have been someone who had been fooled by the counterfeit and decided to get rid of it by passing it on to some one else."

"I wish he had asked us to change one of his counterfeit tens, instead," mourned Joe. "We would have been five dollars to the good."

CHAPTER III

The Hardy Boys at School

If the boys had any lingering hopes that their school chums would not hear of the manner in which they had been fooled, these hopes were quickly removed next morning.

Scarcely had Frank and Joe ascended the concrete steps of Bayport High than Chet Morton, a stout chubby boy of about sixteen, one of their closest friends, a lad with a passion for practical jokes, came solemnly toward them with a green tobacco coupon in his hand.

"Just the fellows I'm looking for," he chirped. "My great-grandmother just died in Abyssinia and I'm trying to raise the railway fare to go to the funeral. How about changing this hundred?"

There was a roar of laughter from about a dozen boys who were standing about, for Chet had evidently acquainted them all with the affair of the previous day. How he had learned of it, Frank and Joe could not imagine. They grinned good-naturedly, although Joe blushed furiously.

"What's the matter?" asked Chet innocently. "Can't you change it? You don't mean to tell me you can't change my hundred dollar hill? Please, kind young gentlemen, please change my hundred dollar hill, for if you don't I'm sure nobody else will and then I won't be able to go to my great-grandmother's funeral in Abyssinia." He wiped away an imaginary tear.

"Sorry," said Frank gravely. "We're not in the money-changing business."

"You mean you're not in it any more," pointed out Chet. "You were in the business yesterday, I know. What's the matter – retire on your profits?"

"Yes, we quit."

"I don't blame you." Suddenly Chet struck an attitude of exaggerated surprise. "Why, bless my soul, I do believe this bill is bad!" He peered at the flimsy tobacco coupon very closely, then whipped a small magnifying glass from his pocket and squinted through it. At last he raised his head, with a sigh. "Yes, sir, it's bad. It's counterfeit. One of the cleverest counterfeits I ever saw. If it hadn't been for the fact that there is no hundred dollar mark on it and if it hadn't been that there is a picture of the president of the El Ropo Tobacco Company instead of George Washington, I'd have been completely fooled. Isn't it lucky that you boys didn't change it for me? Isn't it lucky? Congratulations, young sirs. Congratulations!"

He shook Frank and Joe warmly by the hand, in the meantime keeping a very solemn face, while the other lads surged about in a laughing group and joined in the "kidding."

They jested unmercifully about the incident of the counterfeit five dollars, but the Hardy boys took it all in good part. The news had leaked out through Mr. Moss, who had told Jerry Gilroy, one of the Hardy boys' chums, about the affair just a short while after they had left the store the previous afternoon. Jerry had lost no time acquainting Chet and the others with the details.

"If you keep on changing money for strangers you won't have much left out of those rewards," declared Phil Cohen, a diminutive, black-haired Jewish boy who was one of their friends. He was referring to the money the Hardy boys had received in rewards for their work in the Tower Mansion case and for helping run down the smugglers.

"Oh, I guess we still have a few dollars," replied Frank smilingly. "We have enough in the bank to buy a motorboat with, anyway."

"What's that?" asked Chet quickly. "Are you getting a motorboat?"

The Hardy boys nodded. Their chums were immediately interested.

"Put me down for one of the first passengers," shouted "Biff" Hooper, a tall, broad shouldered boy who had just pushed his way through the circle.

"We're thinking of getting one like Tony Prito's," said Joe.

"I wish it was mine!" exclaimed Tony. His father, one of the most respected citizens in the Italian colony of Bayport, owned a speedy motorboat which had proved of great service to the Hardy boys in their conflict with the smugglers of Barmet Bay. "But if you're getting a boat at all you can't do any better than get one just like it."

"Dad told us last night we could get one as long as we stayed in the bay and along the coast with it. He was afraid we might get ambitious and try crossing the Atlantic."

"Well," remarked Jerry Gilroy, "I see where our summer baseball league is shot to pieces now."

"Why?"

"You'll be out in that boat every minute of your spare time. It was bad enough when you had the motorcycles. You were both always roaming around the country on them, but now we'll never be able to find you at all. There goes the best pitcher and shortstop of my team together."

Jerry looked very glum as he said this, for he was an ardent ball fan and he had been much in the forefront in organizing a league for the summer months. Frank Hardy was one of the best pitchers in the school, and Joe could cover short in a manner that was the envy of his companions, but in spite of their natural ability for the game, the Hardy boys had always shown a preference for outings instead of baseball.

"I'd rather go out for a whole day on a motorcycle or in a motorboat than play a dozen ball games," said Frank.

This was rank heresy to Jerry, who could not bear any reflections on his beloved game.

"Gosh, I don't know what's to become of you two! Can't I count on you for any games at all?"

"Sure you can," promised Frank. "We're not going to live in the motorboat."

"If you go fooling around Barmet Reefs on a stormy day in the old tub you'll die in it, though," snickered Chet.

"That'll be about enough from you," warned Frank, giving him a friendly dig in the ribs. Then, turning to Jerry, he went on: "We'll play on your team, but we won't spend all our time outside of meal-hours in practising."

"Well, I suppose I should be satisfied. We can't have everything. But I'd imagine you'd like to practise."

"They don't need to," declared Chet, "That's why you have to spend all your spare time learning how to catch. Even now you're not much good at it." He winked at Tony Prito, who was standing behind Jerry. "Why, I'll bet you can't catch a measly little fly – like this – look –"

He took a baseball out of his pocket and threw it lightly into the air. It did not go very high and it was a ridiculously easy catch for any one. As for Jerry Gilroy, who was really a star outfielder, it was scarcely worth the effort. He had but to step back a pace and the ball was his.

"Can't I?" he said, somewhat nettled by Chet's words. The ball arched through the air and descended directly toward him. He stepped back, prepared to make the easy catch.

But Tony Prito had caught Chet's wink and knew what it meant, for they had carefully rehearsed the trick between them. As soon asChet had thrown the ball, Tony knelt on his hands and knees on the grass immediately behind Jerry. For all his seeming carelessness, Chet had thrown the ball just far enough so that Jerry would have to step back to make the catch.

Jerry collided with the recumbent figure behind him, he staggered, lost his balance and tumbled over Tony Prito, while the baseball thumped into the grass. The other boys, who had seen the joke from the start, laughed uproariously as Jerry picked himself up and betook himself in pursuit of the already fleeing Tony, while Chet, with an air of vast satisfaction, picked up the baseball.

"I knew he couldn't catch it," he said, with all the airy disdain of a minor prophet.

Just then the gong in the main hall of Bayport High began to clang, summoning the students to their classes, and the boys crowded through the wide doorway.

CHAPTER IV

Another Victim

When he took his place in class that morning, Frank Hardy glanced over at the desk, two aisles away, where Callie Shaw was sitting.

Callie, a brown-haired, brown-eyed miss with a quick, vivacious manner, was one of the prettiest girls attending Bayport high school She was Frank's favorite of all the girls in the city, and each morning he glanced over at her desk and never failed to receive a bright and fleeting smile that somehow made the dusty classroom seem a trifle less drab and monotonous, and when she was not there it always seemed that the day had gotten away to a bad start.

She was there this morning, but she was gazing soberly at her books and she failed to return Frank's glance with her usual smile. This was something so utterly extraordinary that Frank gazed at her, open-mouthed, for a second or so until, recollecting himself, he turned to his own books and proceeded to spend much of the time until recess in a state of helpless wonderment. Like the average boy under such circumstances, he racked his brains trying to recollect what he could have done that might have offended Callie. But there seemed to be no solution to the mystery.

Perhaps she had heard of how he had been fooled by the stranger yesterday. Perhaps she felt contempt for him because he had been so easily outwitted. This was one of his wild surmises, but he rejected it because it was rot like Callie to be angry about anything unless there was good reason for her displeasure. At last lie gave it up and tried to dismiss the matter from his mind, but several times during the morning he cast covert glances in her direction.

But Callie was plainly worried and downcast. She seldom raised her eyes from her books, she answered the teacher's questions in a most abstracted manner, and altogether it appeared that there was something on her mind beyond schoolwork.

When recess came she walked slowly out of the room, not mingling with the other girls. Frank saw her go outside toward the campus, where she sat down on the grass by herself, watching an impromptu basketball game and declining all requests to join in the fun.

He went over to her and flung himself down on the grass beside the girl.

"What's the matter, Callie?"

She looked up at him and smiled faintly.

"Hello, Frank, where did you drop from?"

"I've been sitting right across from you in school all morning and this is the first time you've noticed that I'm alive."

"I'm sorry, Frank. I didn't mean to be rude. I've got something on my mind this morning, that's all."

"Trouble?"

She nodded.

"What about?"

"Money."

He was puzzled by this remark. Callie lived with her cousin, Miss Pollie Shaw, the proprietor of a beauty parlor in the city, and although Miss Shaw was not rich, she made a comfortable living. Therefore, when Frank heard Callie say that she was worried about money he was naturally puzzled. Callie's parents lived in the country, but they sent their daughter frequent remittances to pay the expenses of her education in Bayport.

"What's the matter?" he asked. "Didn't your allowance come?"

"No, it isn't that. I'm all right. It's Pollie. She lost some money. More than she could afford."

"Lost some? How was that?"

"She lost fifty dollars last night."

Frank whistled.

"Whew! That's a lot of money."

"It certainly is. The worst of it is that Pollie had just made the final payment on some new electrical fixtures in the shop and it had left her pretty short of cash. I feel bad about it for her sake."

"How did it happen?"

"A woman came into the store last night and bought some beauty preparations, quite a large order. It amounted to about twelve dollars and she had nothing less than a fifty dollar bill in her purse. Pollie had that much money in the till, for it was near the end of the day, and she didn't like to lose the order, so she changed the bill."

Frank nodded soberly. He knew now what had happened.

"And the money was counterfeit," he said.

"Why, how did you know?" exclaimed Callie.

"I was fooled yesterday myself." Frank then went on to tell Callie how he and Joe had been victimized by the stranger on the station platform. "Dad says there is a lot of this counterfeit money being circulated," he said. "They certainly aren't losing much time in getting rid of it around Bayport. Gee, first a five and now a fifty! I'm sure sorry that Pollie is out that much money."

"Yes, it's a big amount," declared Callie. "Of course, she'll get along, but no one likes to lose that much."

"Did she know the woman?"

"Oh, no. She was a total stranger. She was rather handsome and was well dressed. Pollie didn't suspect anything wrong. As a matter of fact, it wasn't until she picked up the paper after work last night and read that the banks; had issued a warning about counterfeit money that she began to think about it. So she called up Mr. Wilkins, who works in one of the banks, and he came over and took a look at the bill. He said right away that it was no good, although he admitted it was so cleverly done that any one might be fooled by it."

"Just what they said about my five. Did Pollie tell the police?"

"I suppose she has told them by now. But she gave me the bill and asked me to turn ii over to your father."

"Good! Dad happens to be working along those lines just now. Have you got the bill with you now?"

"It's in my purse in the cloakroom. I'll let you have it at lunch hour."

So when school was dismissed at noon Callie gave Frank the counterfeit fifty dollar bill. Frank examined it closely. Like the five dollar bill he and Joe had changed for the plausible stranger the previous day, it was crisp and new. Frank had seen very few fifty dollar bills in his life, either genuine or otherwise, but he realized that this specimen was a very good imitation. The mere fact that such bills are not often seen by the average person no doubt rendered it easier to pass without being readily detected.

"I'll show this to my father," he promised Callie. "I'm afraid it won't do much good Pollie will have to stand her loss, unless she Ban trace the woman who passed the bad bill am her, but perhaps this will help dad find the source of all this counterfeit money."

"Goodness knows how many poor people are being victimized just as Pollie was," said the girl. "I hope they catch the people who are at the bottom of it."

When Joe joined Frank on the school steps Frank told him about the incident at the beauty parlor and of how Pollie Shaw had lost fifty dollars in goods and money to the strange woman.

"Of course," said Frank, "she may have been perfectly innocent in passing that fifty dollar bill, and perhaps she didn't realize it was counterfeit, but I'm beginning to think this gang has a number of people traveling around getting rid of the imitation bills."

"Once they get them into circulation they'll go from hand to hand until the banks check them up. Somebody is bound to lose in the end, and usually it's the honest person who finds out that the money is bad and won't pass it any further. The crooked ones will just try to get rid of it as quickly as they can."

When they reached home Frank told his father about Pollie Shaw and handed over the counterfeit bill.

"So they're dealing in fifties now!" exclaimed Fenton Hardy, as he looked at the money.

"Do you think it's made by the people who turned out that bad five that we got stung on?" Joe asked.

Mr. Hardy drew a magnifying glass from his vest pocket and make a close scrutiny of the bill. "It seems to have been printed on the same press but I'm not sure," he announced at last. "These things are so cleverly done that it would take an expert to notice any differences." He proceeded then to examine the five dollar bill, comparing it closely with the fifty, and at last he put the glass back into his pocket.

"I'm practically certain that these bills were issued from the same press. The paper seems to be of the same kind, just a shade lighter than the paper used in genuine money, and there are certain little differences in the engraving that are almost identical on each bill. Miss Shaw won't mind if I keep this, will she?" he asked Frank.

''She asked me to give it to you."

"I'll send both these bills to an expert in the city and we'll get his opinion on it."

Mrs. Hardy, a pretty, fair-haired woman sighed.

"I'm sure I don't know what the world's coming to," she said, "when men will make bad money and know that poor people are going to lose by it. It's a shame."

"There's nothing some of them won't stop at when it comes to filling their own pockets," declared her husband. "But perhaps when the expert sends me his report on these bills I'll have something more to work on. If it turns out that there is one central gang circulating his money we'll all have to be on the lookout."

CHAPTER V

Curing the Joker

Hard work in school occupied the attention of the boys for the rest of the week, for examination time was near, and even Jerry Gilroy was obliged to dismiss baseball from his mind in a frantic attempt to catch up with his geometry and Latin, that somehow appeared to keep perpetually ahead of him. Frank and Joe sweated over the ablative absolute and grumbled over the heroic exploits that could be resurrected from the deathless lines of Caesar and Virgil if one could but distinguish verbs from nouns, and wondered, as schoolboys have wondered from time immemorial, why they should be obliged to concern themselves with things that happened two thousand years ago and more when they might better be outside playing.

When Friday night came they emerged from the haze of declensions and vocabularies, axioms and theorems, equations and symbols in which they had been engulfed all week and decided that Saturday should see them as far away from school as possible.

"Let's get out of the city altogether," suggested Frank, as the Hardy boys left the classroom on Friday afternoon. "What say we all go for a hike out into the country?"

"Suits me," agreed Chet. "No motorcycles either. Let's walk."

"Good idea," Jerry Gilroy approved. "Unless," he said hopefully, "you fellows would rather come up to the campus and have baseball practice."

"Another smart remark like that out of you and I'll practice my famous left hook on your jaw," warned Biff Hooper, squaring off in a pugilistic attitude. "We don't want to see or hear of this school again until Monday morning, and that'll be too soon."

"All right, all right," said Jerry placatingly. "I just thought I'd mention it."

"And I just think you'll forget about it," said Chet. "You'll come along on this hike with us. Here, have an apple and keep quiet."

He dug into the inexhaustible recesses of his pockets and produced a slightly shopworn apple, which he thrust into Jerry's hands, ''There, see if that'll keep you quiet for a while."

Jerry, who could never resist anything in the nature of food, accepted the donation eagerly.

"Where shall we go on this hike?" he asked, raising the fruit to his lips.

"I was thinking we could go up to Carl Stummer's farm," suggested Joe. "Mother was* saying she wondered if Stummer would let her have any cherries to can this year. This would be a good time to ask him."

"Suits me," said Jerry, taking a prodigious bite of the apple.

Then an expression of pained surprise crossed his face to be replaced by a look of ghastly realization. Tears spurted to his eyes and his jaws worked convulsively. Then he emitted a gurgle of agony, spluttered, spat out the apple and began to dance around on the pavement, waving his arms in the air.

"Indian war dance!" commented Chet gravely, clapping his hands. "Fine work, Jerry. Do it again."

"Pepper!" spluttered Jerry. "I'm burning up! Water!"

"Call the fire brigade," advised Chet, bursting into a shriek of laughter.

The other lads gazed at their companion in amazement until his wild antics became too much for them and they all roared as Jerry continued his frantic splutterings. Wildly, the victim turned toward the school again. There was a water fountain near the front door and he headed toward it, but his eyes were so full of tears from the mouthful of red pepper that he had gulped when he bit into the hollow apple that he did not see a flower-bed in his path.

Jerry stumbled over the wire border and sprawled full length among the flowers.

The janitor, a cantankerous individual named MacBane, had been standing near by watching the performance with a broad grin on his usually dour features. But when he saw Jerry fall into his precious flower-bed he gave a roar of fury.

"Awa' wi' ye!" he bellowed. "Awa' frae ma flowers, ye young limb! I'll hae ye reported!"

MacBane always lapsed into broad Scotch when his temper was aroused. The rest of the boys scattered, fearing the wrath to come. Jerry managed to scramble out of the flowerbed just as the janitor reached him. He jumped out of reach of the outstretched hand, with the result that MacBane lost his balance and overstepped the border, treading on some choice blossoms and getting tangled up in the wire.

Jerry made for the fountain and was already taking deep gulps of the cool water when Mac-Bane, now spluttering unintelligible phrases that could only have been understood in the remotest reaches of Caledonia, got out of the flower-bed and thundered toward him. With a longing glance at the spouting water, for his raging thirst was not yet appeased, and with a fearful glance at the approaching janitor, Jerry turned and fled.

He joined his laughing companions at the street corner, and with a shame-faced air admitted that the joke had been on him. MacBane gave up the chase, vowing threats of vengeance on the following Monday.

"He'll forget all about it by then," assured! Phil.

"I won't forget about it," declared Jerry. "Next time anybody offers me an apple I'll ask for an orange instead. You can't very well fill that with pepper. I'll get even with you, Chet."

"You're welcome to try," replied the practical joker cheerfully. "But in the meantime let's plan this trip for to-morrow."

As a result of their arrangements, the Hardy boys and their chums met in the barn back of the Hardy home early the next morning, all outfitted for a hike into the country. Each lad carried a substantial lunch, their mothers realizing that the noonday meal by the roadside is one of the chief features of such an outing. Phil and Tony were late, and the other boys put in the time by exercising in the Hardy boys' well equipped gymnasium, to which purpose the barn had been converted. Biff Hooper practiced left hooks and uppercuts with desperate intensity and battered the punching bag until it hummed; Chet almost broke his neck attempting some complicated maneuvers on the parallel bars that were meant as an imitation of a circus bareback rider; Jerry contemplated his lunch and wondered if it were too soon after breakfast for a piece of pie.

Phil Cohen and Tony Prito arrived together and the boys started off at last, trudging along the broad highway in the early morning sunlight, whistling away in the best of spirits They were decorous enough while they were in the city limits, but once they struck the dusty country roads their natural activity asserted itself and they wrestled and tripped one another, ran impromptu races, picked berries by the roadside and laughed and shouted without a care in the world.

The road skirted the Willow River, which ran among the farms and hills back of Bayport, through a pleasant, pastoral country. Toward the middle of the morning the boys left the road and struck out beneath the trees toward a secluded spot on the river, where they enjoyed a swim. For over an hour they splashed about in the cool water. Chet was the first to come ashore, and the others would have remained much longer had it not been for the discovery that their thoughtful companion, after getting dressed, was busying himself in the time-honored pastime of tying their clothes into knots.

Whereupon they scrambled out of the water and chased the chubby one into the shelter of some bushes, whence they were unable to pursuehim further because the thorns hurt their bare feet and they were forced to retreat, hopping, toward the river bank while Chet jeered at them from the covert.

"Chaw on the beef!" he cried, in the time honored way.

"Just you wait!" spluttered Joe, chewing on a knot with all his might.

"Am waiting," was the cheerful retort of the joker.

"We'll skin you alive!" muttered Jerry.

"And salt you," added Frank.

But when they had untied the knots they gave chase and the plump jester was soon winded, although he had a good start. He puffed and panted as they chased him down the road in the dust. They caught up to him at the entrance to the lane leading into Carl Stummer's farm, forcibly divested him of hishiking-boots, socks and necktie and proceeded to wreak revenge.

"We'll cure yon of practical jokes for a while," promised Frank, with a grin, as he cast oneboot into a field wherein a bad-natured bull was grazing, and the other into a field at the other side of the lane, with a heavy growth of thistles around the fence.

"See if you're as good at untying knots as you are at tying them," added Jerry, as he twisted Chet's necktie into a veritable Chinese puzzle.

"And now see how it feels to walk around in jour bare feet," suggested Phil, as he hung one of Chet's nocks over the limb of a tree some distance down the road and placed the other in the middle of a clump of brambles.

Biff Hooper and Tony then released the protesting Chet. They had been sitting on him in the middle of the lane while the others were performing their kindly offices. "We'll see you down at the farm," said Biff airily, as the lads went chuckling down the lane in the direction of Stummer's place.

Spluttering and vowing threats, Chet was forced to retrieve his clothes. When he sought to regain his boot from the pasture the bull saw Mm and rushed toward him with a bellow. Chet, in bare feet, just reached the fence in time and tumbled over into the bushes with the rescued boot. Then he had to step gingerly through the thistle patch in the other field before he could get the other boot. After that he had to climb a tree before he could reach the sock, and go plunging through the brambles before he could regain the other. When the laughing boys last saw him he was sitting by the roadside picking thistles from his feet and gazing hopelessly at his necktie.

"He's cured for a while now," chuckled Joe, as the boys came up into the barnyard of Stummer's farm.

"Cure him? Never!" exclaimed Frank "He'll be making us all step before the day is out."

CHAPTER VI

The Old Mill

Carl Stummer, a lanky, shambling old farmer with drooping shoulders, a drooping mustache end a drooping pipe, was just coming in from the fields when the boys came through the barn yard gate.

How he managed to chew a straw and smoke a pipe perpetually at the same time was always a fascinating mystery, but he could do it and always seemed to derive a great deal of satisfaction from the feat, stopping only to change the straw or fill the pipe at intervals. Some people had been known to have seen him without the straw and some had seen him without the pipe, but no one had ever seen him without one or the other.

Chet Morton always stated it as a grave fact that Carl Stummer slept with his pipe in his mouth and a supply of fresh straws constantly his bedside and that he changed them in his sleep.

" 'Lo, boys!" he called, taking a firmer grip of the pipestem. "And what brings you here?"

"How's the cherry crop, Mr. Stummer?" asked Frank.

"Fair to middlin'," replied Mr. Stummer doubtfully.

This was a good sign, as Carl Stummer was rarely known to express an encouraging opinion about anything. If he said crops were poor, one might be reasonably certain that they were really fair. If he said they were "fair to middlin' " it might be inferred that they were excellent.

"Mother wants to know if you can let her have cherries to can this year."

Mr. Stummer chewed with relish at the straw.

"Most probably she kin," he agreed.

''She wanted to speak for them so that you'd keep her in mind at cherry-picking time."

"I'll remember," promised Stummer. "Mrs. Hardy has always been a good customer of mine. You tell her she can have all of them sherries that she wants."

"Thanks, Mr. Stummer. That's all we called about."

The farmer looked at them. His hands were plunged deep in the pockets of his faded overalls. The straw waggled beneath the drooping mustache.

"Out for a hike?" he ventured.

"Yes. We thought it would be a good day for it."

"Yeah, pretty fair day for hikin'," agreed Mr. Stummer, glancing at the sky to make sure. "Where you thinkin' of goin'?"

"Oh, we don't know. Just around the country."

"Yeah? Not goin' down by the old mill, are you?"

"Turner's old mill?" asked Joe. "Down by the deserted road?"

"That's the place. Down by the river."

"Well, we hadn't thought particularly about going down there. Why do you ask?"

The straw waggled more violently than ever. Mr. Stummer took a long drag at the pipe, which was in imminent danger of going out.

"Oh, I dunno," he said, with a reflective sigh. "Just thought I'd say somethin' about it. I wouldn't go down there if I was you."

"Why not?" inquired Frank. "I know the place is deserted and it's almost falling down, butwe can keep out of danger, can't we?"

"It ain't deserted now."

"What do you mean?"

"There's three fellows running the mill now, Funny fellows they are. Been there for a couple of weeks."

The boys looked at one another in surprise. Turner's flour mill was located on a wild part of the Willow River. It had once been on a main road, but the construction of a new highway had left it on a deserted loop which was now seldom traversed. The mill had been abandoned for several years and seemed to have outlived its usefulness. No one had ever expected that the mill wheel would turn again.

"Are they running it as a flour mill?" asked Frank.

Stummer nodded.

"They don't do much outside grindin'. I sent 'em some of my wheat, but their prices was too high. They nearly skinned me alive, so they don't need to expect any more trade from me. I'll send my grain into Bayport after this, where I've always been sendin' it."

"How do they expect to make a living then?"

"They ain't lookin' for trade from the farmers. Matter of fact, I don't think they want it. They told me they're gettin' up some new kind of breakfast foods that the doctors are all goin' to take up. There's somethin' secret about it," went on Stummer, warming to the mystery. "They ain't sayin' anything until, they get their patents. Why, they won't ever let a man go through the mill."

"Three men, you say?"

"Yeah. Three fellers. Sort of onpleasant lookin' chaps. And there's a boy there too. I forgot about him. Looks somethin' like you," he said, pointing to Joe.

"Have you ever seen any of them before?"

Stammer shook his head.

"I guess they come from the city," toe Hazarded. "They come away down here so they could be quiet and work at this here breakfast food stuff of theirs without bein' bothered. That's why I said you shouldn't go down there. They don't like people hangin' around."

"Makes me curious to see the place," put in Jerry.

The other boys gave murmurs of agreement.

"Go along if you like," said Stummer, shrugging his shoulders. "It ain't none of my affair, Just thought I'd tell you, that's all. They don't like strangers around."

"We won't bother them," promised Frank "What do you say, fellows? Should we take atrip around that way or should we not?"

As usual, the mere fact that something of a mystery surrounded the old mill made all the boys eager to turn their steps in that direction.

"We'll go down the old road, anyway," said Joe. "I'd like to get a look at the place. It'll give us somewhere to go."

"Sure," agreed Phil. "We can eat our lunch on the way."

"The vote seems to be in favor of it," said Frank, with a smile.

''Well," drawled Stummer, chewing vigorously at the straw, "don't blame me if you get chased away from the mill. I've warned you."

His eyes twinkled. His whole purpose in telling the lads of the mystery that surrounded the mill had been to send them in that direction, for he realized the attraction the place would have for the boys when they knew that the mill was running again. He was rather curious, too, about the three men who were in. charge of the place and he thought that perhaps the boys might pick up some information that he had been unable to get.

"Have a good hike," he said, as he turned to go back to the farmhouse, ''Don't get into any trouble."

"We won't," they assured him, and forthwith started back down the lane.

They met Chet, who had by this time managed to retrieve his belongings and was trudging along in the dust meditating ways and means of getting even with his companions, He was not vindictive and he had taken the joke in good part, grinning cheerfully as he saw them approach.

"Think you're pretty smart, don't you?" he said, in mock resentment, as they came near. "I've got so many thistles in my feet you'll have to carry me home now."

With that he began to limp in an exaggerated manner, as though he had been completely crippled by his efforts to regain his socks and shoes.

"We wouldn't carry you to the end of the lane," said Frank promptly. "You'd better keep your feet moving if you want to come with us."

"Where are you going?"

"Down to the old mill. Stummer tells us the place is running again."

"Hurray!" shouted Chet. "I'll race you!" and, forgetting all about his tender foot-soles, heled the crowd in a mad race toward the main road.

CHAPTER VII

In the Mill Race

An hour later, the Hardy boys and their churns reached the vicinity of the old mill.

They had lunch in the shade of the trees along the deserted road, and it was early in the afternoon when they arrived at the top of the hill that overlooked the river.

The old mill was a sturdy structure that had once been strong and imposing but was now weatherbeaten and showed the ravages of the years. The mill wheel turned slowly, creaking painfully as though it objected to being forced to labor again after its long rest.

Outside the front door, they could see three figures, two men and a boy. At that distance it was impossible to distinguish their features, but as the lads descended the hillside and drew closer they saw that the men were middle-aged fellows, far from reassuring in appearance.

Because of Stummer's remarks, the Hardy boys and their chums took good care to keep to the shelter of the bushes as they went along the abandoned roadway, now overgrown with weeds and undergrowth. Their approach was not noticed, and at last they were standing not more than a hundred yards away from the mill, effectually concealed by the trees and shrubs.

"I don't like the looks of the men," remarked Prank, in a low voice.

"Neither do I," agreed Joe.

One of the men was apparently about fifty years of age. He had a dirty, greying beard and be wore spectacles. He was clad in a torn and stained pair of overalls and his sleeves were rolled to the elbows, revealing his blackened arms.

"For a miller, there's mighty little flour on his hands," commented Frank. "He looks more like an automobile mechanic."

The other man, who looked older, was similarly attired, but he was of a more benevolent appearance. He did not wear glasses and his shaggy brows almost hid a pair of keen, sharp eyes. He fondled his long white beard reflectively as the other man talked to him in low tones.

The boys could not overhear what the pair were saying, but they saw the boy, a fair, curly-headed youth of about fifteen, in ragged clothing, look up at the older man and say something to him.

Instantly the old fellow lost his look of benevolent reflection. He gave the boy a cuff on the ear that almost staggered him.

"Be off with you!" he ordered harshly. "Go away and play. Don't be hanging around here while we're talking."

He spoke so loudly that his words could he clearly heard by the lads hidden in the bushes. The curly-headed boy stood his ground, and evidently repeated what he had said before, for the old man at once became furious.

"Go away and play, I tell you!" he shouted in shrill tones. "I'll call you when I need you. And be sure you come in a hurry when you hear me."

He reached behind him for a heavy cane that was leaning beside the doorway and he struck out viciously at the lad with it. But the boy dodged the blow and ran off toward the mill race, while the old man watched him go, muttering imprecations.

"Leave him alone," said the other man in a. guttural voice. "We've got other things to attend to than that brat."

"He's a nuisance. I'll whale the hide off film when he comes back."

"Leave him alone. Markel is waiting for us. Let's go inside."

''All right – all right," muttered the old man peevishly. He turned and followed the other through the doorway.

"Nice tempered old chap," remarked Jerry, when the pair had disappeared into the mill.

"I'll say he is," declared Joe. "I don't think either of them is up to much."

"The young fellow looks all right," Chet said. "He looks as if he has a sweet life here with those men."

Phil said:

"I thought Stummer told us there were three men running the mill."

"They said something about Markel," Frank pointed out. "He's the man who is waiting for them inside the mill. That must be the other partner."

"Let's go up and talk to the kid," suggested Joe. "Perhaps we can dig something out of Mm about those men. They don't seem to treat him very well, anyway."

The boy was walking along the side of the old mill race. The waters were very swift at this point, for the current was strong and the river was deep. The boy was trudging along the weatherbeaten planks, with his hands in his pockets, looking very disconsolate.

"Lonely looking boy," observed Tony. 'They told him to run away and play. He looks as if he'd never played in his life."

"We'll go over and talk to him," Frank decided, "If those old chaps say anything to us about being around here we'll ask them to quote some prices on having some milling done."

"I can do that!" exclaimed Chat. "Dad's a farmer, and he's often said he wished the, old Turner mill was running again so he wouldn't have to haul his grain so far."

The boys emerged from the bushes and crossed the weed-grown open space near the front of the mill. The other lad had not yet seen them. He was standing by the mill race,, some distance below, gazing into the water, now and then raising his head to look at the clacking wheel that turned monotonously in showers of dripping water.

"I'm curious about this patent food story," Frank said. "It's queer there wasn't anything in the papers about it. Nobody except the farmers, like Stummer, seems to have heard about the mill being taken over."

"Oh, probably they want to keep it to themselves until everything is ready," Jerry pointed out. "I'll bet you're beginning to see some kind of mystery in this already, Frank, Chances are we'll just get kicked off the premises for our pains."

"Oh, I don't think there's any mystery about it," said Frank, with a smile. "But I'm just curious to know what it's all about."

"No law against that," Phil agreed. "If this breakfast food invention of theirs turns out to be something wonderful that makes us all live about twenty years longer, we can say we were among the very first to know about it."

By this time they had drawn closer to the* mill race, and the boy standing there had raised his head and seen them.

He was a good-looking fellow, not unlike Joe Hardy in appearance, as Carl Stummer had pointed out. But his face was pinched and drawn and there was a melancholy expression in his eyes.

"Looks as if he hadn't had a square meal in a month," Jerry remarked.

The boy turned and began to move toward Frank and Joe.

He had gone only a few paces, however, when they saw him suddenly stumble. He had stepped upon a loose stone that had rolled from beneath his foot.

He wavered uncertainly, striving to regain his balance. Then, with a shrill cry, he toppled over into the mill race and fell with a spl