The underlying forces that determine the exchange rate between two currencies are the supply and demand resulting from commercial and financial transactions (including speculation). Foreign-exchange supply and demand schedules relate to the price, or exchange rate. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which assumes free-market or flexible exchange rates.

Figure 1

Before examining this figure, we need to define two terms. Depreciation (appreciation) of a domestic currency is a decline (rise) brought about by market forces in the price of a domestic currency in terms of a foreign currency. In contrast, devaluation (revaluation) of a domestic currency is a decline (rise) brought about by government intervention in the official price of a domestic currency in terms of a foreign currency. Depreciation or appreciation is the appropriate concept to deal with floating, or flexible, exchange rates, whereas devaluation or revaluation is appropriate when dealing with fixed exchange rates.

In the dollar-pound exchange market, the demand schedule for pounds represents the demands of U.S. buyers of British goods, U.S. travelers to Britain, currency speculators, and those who wish to purchase British stocks and securities. It slopes downward because the dollar price to U.S. residents of British goods and services declines as the exchange rate declines. An item selling for £1 in Britain would cost $2.00 in the U.S. if the exchange rate were £1/$2.00 U.S. If this exchange rate declined to £1/$1.50 U.S., the same item is $.50 cheaper in the United States, increasing the demand for British goods and thus the demand for pounds. The supply schedule of pounds represents the pounds supplied by British buyers of U.S. goods, British travelers, currency speculators, and those who wish to purchase U.S. stocks and securities. It slopes upward because the pound price to British residents of U.S. goods and services rises as the $ price of the £ falls. Assuming an exchange rate of £1 /$2.00 U.S., a $2.00 item in the U.S. costs £1 in Britain. If this exchange rate declined to £1/$1.50 U.S., the same item is 33 percent more expensive in Britain, decreasing the demand for dollars to buy U.S. goods and thus reducing the supply of pounds. The equilibrium exchange rate in Figure 1 is £1/$2.00 U.S. The amounts supplied and demanded by the market participants are in balance.

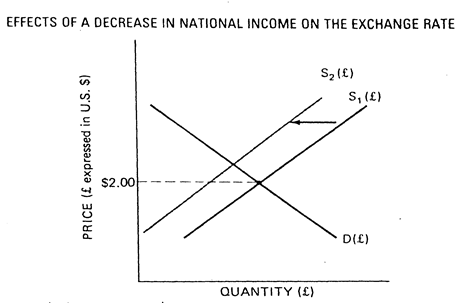

Figure 2

To understand better the schedules, several of the factors that might cause these curves to shift are discussed next. If there is a decrease in national income and output in one country relative to others, that nation's currency tends to appreciate relative to others. The domestic income level of any country is a major determinant of the demand for imported goods in that country (and hence a determinant of the demand for foreign currencies). Figure 2 shows the effects of a decline in national income in Britain (assuming all other factors remain constant). The decrease in British income implies a decrease in demand for goods and services (both domestic and foreign) by British people. This reduction in demand for imported goods leads to a reduction in the supply of pounds, which is shown by a leftward shift of the supply curve in Figure 2 (from S  to S

to S  ). If the exchange rate floats freely, the British pound appreciates against the U.S. dollar. If the exchange rate is artificially maintained at the old equilibrium of £1/$2.00 U.S., however, a balance-of-payments surplus (for Britain) likely results.

). If the exchange rate floats freely, the British pound appreciates against the U.S. dollar. If the exchange rate is artificially maintained at the old equilibrium of £1/$2.00 U.S., however, a balance-of-payments surplus (for Britain) likely results.

Figure 3

In Figure 3, an initial exchange-rate equilibrium of £1/$2.00 U.S. is assumed. Now presume the rate of price inflation in Britain is higher than in the United States. British products become less attractive to U.S. buyers (because their prices are increasing faster), which causes the demand schedule for pounds to shift leftward (D  to D

to D  ). On the other hand, because prices in Britain are rising faster than prices in the U.S., U.S. products become more attractive to British buyers, which causes the supply schedule of pounds to shift to the right (S

). On the other hand, because prices in Britain are rising faster than prices in the U.S., U.S. products become more attractive to British buyers, which causes the supply schedule of pounds to shift to the right (S  to S

to S  ). In other words, there is an increased demand for U.S. dollars in Britain. The reduced demand for pounds and the increased supply (resulting from British purchases of U.S. goods) mandates a newer, lower, equilibrium exchange rate. Furthermore, as long as the inflation rate in Britain exceeded that in the United States, the British pound would continually depreciate against the U.S. dollar.

). In other words, there is an increased demand for U.S. dollars in Britain. The reduced demand for pounds and the increased supply (resulting from British purchases of U.S. goods) mandates a newer, lower, equilibrium exchange rate. Furthermore, as long as the inflation rate in Britain exceeded that in the United States, the British pound would continually depreciate against the U.S. dollar.

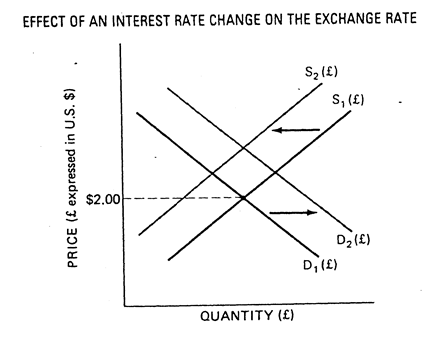

Differences in yields on various short-term and long-term securities can influence portfolio investments among different countries and also the flow of funds of large banks and multinational corporations. If British yields rise relative to others, an investor wishing to take advantage of these higher interest rates must first obtain British pounds to buy the securities. This increases the demand for British pounds shift the demand schedule in Figure 4 to the right (D  to D

to D  ). British investors are also less inclined to purchase U.S. securities, moving the supply schedule of pounds to the left (S

). British investors are also less inclined to purchase U.S. securities, moving the supply schedule of pounds to the left (S  to S

to S  ). Both activities raise the equilibrium exchange rate of the British pound in terms of U.S. dollars.

). Both activities raise the equilibrium exchange rate of the British pound in terms of U.S. dollars.

Figure 4