Dare to read: Нэнси Дрю и Братья Харди

(https://vk.com/daretoreadndrus)

ПРИЯТНОГО ЧТЕНИЯ!

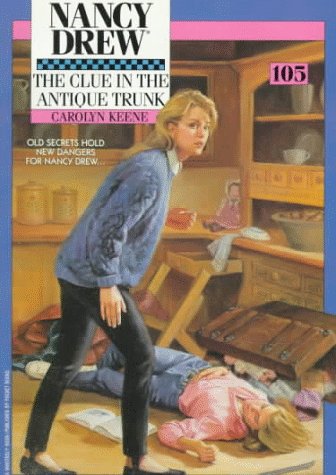

Carolyn Keene

Nancy Drew Mystery Stories: Volume One Hundred-Five

The Clue in the Antique Trunk

Copyright, 1992, by Simon & Schuster

In a town as pretty as a picture postcard, Nancy seeks the key to a picture-perfect crime! Nancy has come to White Falls, Massachusetts, to visit her former neighbor, Vera Alexander. The town is rich in history, and Vera wants to preserve a piece of its past. But her plan to convert the old Caulder Cutlery factory into a museum turns suddenly ominous when someone threatens her life.

Why was Vera's antique trunk stolen? What dark secrets has she unwittingly disturbed? The answers are hidden in the past. Fifty years ago the owner of Caulder Cutlery was killed by his own knife – and Nancy knows that before she can solve the present-day case, she must first uncover the haunting truth behind an old-fashioned murder.

Crime in the Country

“Wow! I had no idea the Berkshires were so beautiful,” said Bess Marvin, pausing in the doorway of the bus. She brushed her blond hair out of her eyes and gazed at the snow-covered foothills that rose up before her in gentle waves.

“The evergreen trees smell great,” Nancy Drew added, inhaling deeply. “Especially after two hours of breathing bus exhaust fumes and seat vinyl the whole way from Boston.” She smoothed her shoulder-length reddish blond hair and stretched her long, slender figure.

Bess’s cousin, George Fayne, gave Bess a nudge from behind. “Hey, would you mind getting out of the doorway? I’d like to get a look at this great view, too, if it’s okay with you.”

“Oh, sorry.” With an embarrassed giggle, Bess lugged her big suitcase down from the bus and joined Nancy on the pavement. George quickly followed. A moment later, the bus door closed and the bus took off down the road, belching diesel fumes from its exhaust pipe.

“So this is White Falls, huh?” George set down her nylon bag and looked around. “No wonder Vera decided to move here.”

The girls stood in a parking lot in front of a rambling wooden inn with a gabled roof. A row of old-fashioned storefront buildings stretched along the road beyond the inn. Several smaller roads wound up into the foothills, where Nancy saw a white church spire and scattered wood-frame houses. A river ran along the opposite side of the main road, its banks covered with snow.

“Vera’s only lived here for two years,” Nancy said. “She left River Heights when she inherited a house from her great-aunt here. Now she says she could never think of living anywhere else.”

Nancy had remained in touch with her former neighbor, Vera Alexander, after Vera had moved to the small town in northwestern Massachusetts. When Vera had invited Nancy and her friends to White Falls for a traditional crafts fair, the girls had jumped at the chance.

|

|

“It looks like the perfect place for a crafts fair,” Bess said. “I feel as if I’ve been plunked down in one of those paintings of old New England—you know, with sleigh rides and everyone cutting logs and feeding farm animals.”

George groaned. “Nancy, can’t you do something with her?”

“Actually, all that stuff is the reason Vera decided to move here,” Nancy said. She couldn’t help laughing at her friends. Although they were cousins and best friends, Bess and George were not at all alike. Blond, blue-eyed Bess’s favorite activities were shopping and eating, but dark-haired George was more practical, with the tall, lithe build of a natural athlete.

Nancy flipped up the collar of her aqua ski parka. “But don’t forget, the crafts fair isn’t the only reason we’re here. Vera was pretty vague about the details, but she did mention that someone might be trying to ruin the fair.”

“Did she say why?” Bess asked.

Nancy shook her head. “That’s one of the things I hope Vera can tell us. She should be here any minute.”

Just then, a car horn sounded behind them. Nancy turned and saw a white minivan pulling to a halt in the parking lot. The driver’s door flew open, and a tall, slender woman in her thirties hopped out, her long black hair spilling around the collar of her red ski parka.

“Nancy!” the woman called, running over and giving her a hug. “I’m so glad you could come.”

“Me, too, Vera,” Nancy said with a grin. “It’s great to see you. You remember Bess and George.”

Vera shook the girls’ hands and said, “Sorry I’m late, but I had to drop off some speakers for tonight’s barn dance.”

Bess’s blue eyes lit up. “A barn dance?” she asked. “You mean square dancing?”

“You bet,” Vera told her. “I thought it would be a good way to kick off the crafts fair. There’s a maple syrup boil tomorrow, the crafts workshops on Saturday, and then a big auction on Sunday.”

“Sounds great,” George said.

“It ought to be.” Vera’s smile faded as she added, “As long as nothing happens to ruin it, anyway.”

Nancy gave Vera a sympathetic look. “What makes you think something will happen?” she asked.

With a sigh, Vera reached for Bess’s suitcase. “Here, let’s get your stuff into the van. I can explain while we drive to my house.” A few minutes later, Nancy was seated beside Vera in the van’s front seat. Bess and George settled on the bench seat behind them.

“The whole reason I decided to organize this crafts fair was to raise money for a pet project of mine,” Vera began as she pulled out onto the road that ran along the river. “I want to open a museum, dedicated to the local people and their history.”

“I remember you mentioned that in your letter,” Nancy said. “You’re going to renovate an old building for the museum, right?”

|

|

“It sounds like a terrific idea,” Bess put in.

Vera smiled ruefully at Bess in the rearview mirror. “I’m not sure everyone agrees with you. About a week ago, I started receiving threatening phone calls telling me that if I don’t back off the project, someone will make sure my museum never opens. The voice is always muffled, and I can’t tell if it’s a man or a woman.”

“And you think whoever it is might ruin the fair so you won’t have enough money to fix up the building,” George guessed.

Vera nodded. Nancy could see that Vera was definitely upset about the threats.

“Do you have any idea who’s making the calls?” Nancy asked.

Vera took a deep breath and let it out slowly. “There are some people who seem to be against the project—or maybe I should say one person in particular.”

Leaning forward on the bench seat, Bess asked, “Who’s that?”

“A real estate developer named Rosalind Chaplin. If you ask me, Roz is much more concerned with making a buck than with preserving White Falls’s heritage. She’s constantly tearing down beautiful old buildings and replacing them with modern monstrosities that have no character whatsoever.

“Needless to say,” Vera continued, her dark eyes flashing with indignation, “Roz had different plans for my museum site. She wanted to bulldoze the old building and put up condos for the ski crowd. When they put it to a vote, the town decided on the museum, but Roz seems to hold it against me personally that her plan wasn’t chosen.”

“Hmm,” Nancy said. “I’ll definitely keep my eye on her. Is there anyone else you can think of who might have a grudge against you?”

Vera shrugged. “Not offhand. New Englanders are a tough bunch to figure out, though. They tend to keep their thoughts and feelings to themselves, especially around strangers.”

“Oh, look!” Bess exclaimed, pointing. “There’s one building that Roz Chaplin hasn’t gotten her hands on yet.”

Looking out the van window, Nancy saw a large stone building perched on the far bank of the river, just above a crashing waterfall. Covered with ivy and nestled into the snowy woods, the building looked to Nancy as if it had been there since the beginning of time.

“Well, at least someone around here has good taste,” Vera said, a wide smile spreading across her face. “You’re looking at what will one day be the White Falls Historical Museum,” she announced proudly.

“That’s going to be your museum?” Nancy asked, impressed. “It looks as if it has a lot of history of its own.”

“Oh, it does,” Vera told her. “If those old walls could talk, I’m sure they’d have plenty of stories to tell. There was even a murder that took place there, you know.”

|

|

“A murder?” George asked. She looked at the stone building with fresh interest.

“It was a long time ago,” Vera added quickly, glimpsing in the rearview mirror the horrified look on Bess’s face. “The building used to be an old knife factory called Caulder Cutlery. The owner, Zach Caulder, was stabbed to death right in his office, with one of his own knives. The police never did find out who did it.”

“Stop! It’s too gruesome!” Bess exclaimed, covering her ears.

“The factory’s been quiet for over fifty years now,” Vera assured her. “It went bankrupt soon after Zach died, and the town took it over. It’s been empty ever since.”

Vera turned onto a side road that curved up into the hills, away from the river. Drifts of snow lined the road. After rounding a few bends, she pulled the van into a plowed gravel driveway behind a small bright yellow car. “Here we are,” she announced.

Beyond the snow-covered yard Nancy saw a three-story white house with a porch running along the front. Bushy shrubs and huge oak trees separated the house from its neighbors. Warm light glowed from inside the large shuttered windows.

“I think I could get used to staying here,” George said. She, Nancy, and Bess grabbed their suitcases and followed Vera along the short path that had been shoveled and up the stone steps to the porch.

“It’s huge,” Bess added. “Doesn’t it feel strange to be rattling around in such a big house all by yourself?” she asked Vera.

Vera shook her head. “Not really. I know it sounds strange, but all the crafts and antiques I’ve collected over the years make me feel as though I have plenty of company.

“Besides,” she went on, “Julie Bergson, my assistant, is here most days. She’s been helping me organize everything for the museum and the crafts fair. Sometimes I think I wouldn’t be able to find my own head without her help.” She nodded to the yellow car in the driveway. “Julie must still be working—that’s her car.” As the girls stepped into the front hallway behind Vera, Nancy saw the living room through a doorway. It was very comfortable looking, filled with a jumble of old-fashioned furniture, lamps, pillows, and tables.

“Julie?” Vera called. When there was no answer, she said to the girls, “I’ve converted a big workroom in the back into storage for the fair and museum. She must be back there.”

Vera led the way down a long hallway and through a bright, airy kitchen that looked as if it had recently been painted. “Julie!” she called again. “Why don’t you take a break and—”

Vera’s voice broke off as she reached the doorway on the far side of the kitchen. “Oh, no,” she said with a gasp.

Rushing across the kitchen, Nancy peered over Vera’s shoulder. The big room off the kitchen looked as though a hurricane had ripped through it. Old furniture, tools, dolls, books, and clothing were strewn across the floor. A wooden captain’s trunk lay on its side, with a jumble of antiques spilling out of it.

Then Nancy saw something else that made her breath catch in her throat. To the side of the overturned trunk was a young woman with short blond hair and very pale skin.

She lay motionless on the floor, her eyes closed.

2. Robbed!

“Julie!” Vera cried, running toward the unconscious woman.

Nancy was only half a step behind. Her heart pounding, she bent over Julie and checked her pulse.

“Nancy, is she… dead?” Bess asked from the doorway, the final word coming out in a high squeak.

“No,” Nancy answered with a sigh of relief. “Her pulse is strong, and she’s breathing easily. Quick, get a wet towel from the kitchen.”

A moment later, Nancy was applying the cool, moist towel to Julie’s forehead. The woman looked as if she was in her early twenties, with straight blond hair cut chin-length. As Nancy held the towel to her forehead, Julie groaned, moving her head slightly. Then her eyes fluttered open.

“What—?” Julie blinked a few times, her green eyes clouded with confusion. Then she snapped her head up sharply, looking fearfully from Vera to Nancy, Bess, and George. “Oh, no,” she said in a horrified whisper.

Nancy put a calming hand to Julie’s shoulder. Obviously the young woman was disoriented.

“Take it easy,” Vera said gently, grasping Julie’s hand. “It’s me, Vera, and these are my friends, the ones I told you were coming.” Julie reached up unsteadily and, wincing, touched the back of her head. “But how did—?” She broke off as she saw the disorganized mess of the workroom. “Oh, no,” she said again.

Vera shook her head. “Don’t worry about the mess,” she said. “We’ll clean it up later.”

“No! I mean, it’s not about the mess,” Julie said. Her green eyes flitted nervously around the workroom as she pushed herself to a sitting position. “It’s much worse. Vera, that black lacquered chest, the one that was donated last week—it was right by the desk.”

Vera’s gaze flew to the desk, and the color drained from her face. “It’s gone,” she said.

“I stored some antique patchwork quilts in that trunk,” Vera told Nancy and her friends in a distraught voice. “They were exquisite one-of-a-kind pieces, worth over a thousand dollars each. They were going to be one of the big draws at Sunday’s auction. There’s no way I can replace them.”

“It looks as though whoever made those threats was serious about wanting you to back off the museum project,” George said. She pointed to a rooster-shaped cast-iron weather vane that rested on the floor near Julie. “He or she must have hit Julie over the head with that.”

Vera nodded, blinking back tears. “This is just what I was afraid of. But at least you’re okay, and that’s what really counts,” she said, squeezing Julie’s hand. “I could never forgive myself if…” Her voice trailed off. For an uneasy moment, no one said anything.

“Maybe we should get Julie some water or something,” Bess suggested, breaking the silence.

“That’s a wonderful idea,” Vera agreed. She gave Bess a grateful look. “In fact, I think we could all use some hot cocoa. I’ll make some right away. And, Julie, I want you settled on the living room couch.”

“Bess and I can take care of that,” George offered. With George on one side and Bess on the other, they helped Julie to her feet.

Nancy stayed behind as her friends and Julie left the workroom. “I’ll catch up with you in a minute,” she told Vera. “I just want to take a quick look around here first.”

Nancy carefully scanned the workroom, and the first thing she noticed was a dolly standing next to the door. Its wheels were still wet, as if it had been rolled through the snow outside. There were wet tracks on the floor, too. Nancy followed them into the kitchen and out a back door.

Outside, she picked up the dolly’s tracks in the snow and followed them around the house to where they stopped at the gravel driveway. The thief must have loaded the trunk into a car or truck and simply driven away, Nancy realized. Since the driveway had been plowed, there were no tracks for Nancy to check. And with the thick shrubs on either side of the house, it was unlikely that Vera’s neighbors would have seen anything.

When Nancy went back inside, Vera was measuring cocoa into a pot of steaming milk on the stove. Nancy returned to the workroom and walked slowly around it, being careful to sidestep the dusty toys, old blankets, and ruffly Victorian dresses. The place was a mess, but she didn’t see anything unusual.

With a sigh, Nancy crossed her arms and leaned against the kitchen doorway. If the thief had wanted to steal the quilts, why did he or she make such a mess of everything else, too? Or had the person done this as a warning to Vera to give up her museum project?

“Any luck?” Vera asked. She was holding a tray with five mugs of hot cocoa on it.

“Not really,” Nancy told her. She pointed to the dolly next to the doorway. “At least the thief had the courtesy to return your dolly after using it to cart the trunk out of here,” she said. “I didn’t find any clues as to who did it, though.”

“I feel awful that this happened to Julie in my house,” Vera said, shaking her head. “Things have been hard enough in her life already.”

Nancy caught the worried expression in Vera’s dark eyes. “What happened to her?” she asked Vera.

“Julie told me she used to be … well, a bit troubled back in high school,” Vera replied. “I think she got caught up in a bad crowd. That’s all over with now, though,” she added quickly.

Nancy didn’t want to pry, so she gestured toward the mugs of cocoa on Vera’s tray. “I guess we’d better join the others before those get cold.”

As Vera nodded and disappeared through the kitchen, Nancy took one last look around the workroom. Then something on the doorframe caught her attention. There, about six inches up from the floor, was a deep nick in the fresh yellow paint.

Bending down, Nancy carefully examined the dent. A few slivers of wood with a shiny black covering were stuck to the doorframe. Could they be from the stolen trunk?

Nancy went back to the front of the house and found the others in the living room. Julie was stretched out on the couch, a faded quilt spread over her legs, and a glass of water on the coffee table beside her. Vera perched on an arm of the couch, holding a fresh towel to Julie’s forehead.

“Did you find anything?” George asked. She and Bess were on a love seat by the fireplace, sipping their hot cocoa.

Nancy told them about the nick in the doorway. “It looks as if our thief knocked the chest into the doorway between the workroom and kitchen on his way out.” She glanced at Vera. ”Unless you remember that dent being in the doorframe already.”

Vera shook her head as she held out a full mug of cocoa for Nancy. “I just painted the doorway this morning.”

“It doesn’t tell us who stole the trunk, though,” Nancy said with a sigh. She took the cocoa and sat down in an armchair. “That’s where you come in, Julie. Did you see or hear anything unusual before you were knocked out?”

Julie gave Nancy an apologetic look. “I don’t really remember much. One minute I was logging in some things on our computer inventory. The next thing I knew, I was waking up with you guys standing over me, and the workroom looked like a national disaster area.”

“You don’t even remember hearing the door opening?” George asked.

“Sorry,” Julie said, shaking her head. “My back was to the door. With the hum of the computer, I guess I didn’t hear the person come in.”

Nancy took a sip of her hot cocoa. “It certainly looks as if the attack was aimed at your crafts fair,” she told Vera. “But we can’t rule out other possibilities.” Turning to Julie, she asked, “Do you know of anyone who might want to hurt you?”

“I don’t th-think so,” Julie answered slowly. “No one that I know of, anyway.”

“Goodness me, it’s already four-thirty!” Vera exclaimed, looking at her watch. “The barn dance starts at seven, and I’ve got a million things to do.” Jumping up from the couch, she waved her hand toward the back of the house. “All that mess will have to wait until morning. Julie, you stay right where you are. And as for you girls,” Vera added with a nod to Nancy, Bess, and George, “let’s get you settled in your room upstairs.”

“I can’t dance another step,” George said that evening as she and Nancy finished a square dance. George’s face was flushed from dancing.

Nancy nodded. “We haven’t stopped dancing since we got here. Let’s take a break.”

The two girls thanked their dance partners and stepped to the side of the huge barn. The wide wooden floor planks had been swept clean from the big sliding doors on one side to the hayloft on the other. A low platform was set up along one wall for the musicians. Two fiddle players started in on their next song, and a robust, gray-haired man called out the first steps.

Nancy noticed a boy with curly dark hair being ushered toward the musicians by an older woman. He looked about eleven years old. From the scowl on his face, Nancy guessed that he wasn’t happy about being at the dance. The woman, who looked stern and tight-faced, pushed him up onto the platform.

There was quick applause from the dancers as the boy reluctantly joined the fiddle players, pulled out a harmonica, and began to play along. Though he played quite well, it was obvious from the way he glared at everyone that he was performing against his will. Nancy tapped her foot in time to the music and watched the dozens of couples bowing to each other and beginning to dance. She was glad to see Vera among the dancers, though Nancy noticed her friend’s gaze sliding worriedly around the barn. Julie had recovered enough to attend. She was sitting on the edge of the musicians’ platform.

“What happened to Bess?” Nancy asked George, her eyes skimming over the crowd. “Oh, there she is, next to—”

“The refreshment stand,” George finished with a grin. “Where else would Bess be?”

Nancy grabbed George’s arm and began pulling her toward the tables that had been set up in the alcove beneath the hayloft. “I could use a drink, too. Come on.”

“Hi, you guys,” Bess greeted them, waving a cup in her right hand. “You should try some spiced cider—not to mention these desserts.” She held out a small plate in her other hand. “I couldn’t make up my mind, so I took one of everything.”

“Mmmm, is that a brownie?” George asked, plucking a chocolate square from the plate.

“Save some for me,” Nancy told them. ”I’ll get us some drinks, George.” Leaving her friends, Nancy headed toward a table where there was a punch bowl filled with steaming apple cider.

She was just leaning over to get some cups when a high-pitched yapping at her feet caused her to jump back with a start. Looking down, she saw a miniature white poodle in a frilly plaid outfit, its tail wagging as it jumped around Nancy’s feet.

“Fifi, come here at once!” bellowed a forceful female voice. A moment later, a thin red-haired woman in a red tweed suit and high heels scooped up the dog, holding it protectively in the crook of her arm.

The woman gave Nancy a critical look. “You’re here for this silly crafts fair, I suppose,” she said.

Nancy blinked, slightly taken aback. “Yes, I am,” she answered. “My name is Nancy Drew. I’m a friend of Vera Alexander.”

The woman’s hazel eyes narrowed. “Oh, really,” she said, her voice dripping with disdain.

Nancy just stared at the woman. Clearly she didn’t think much of Vera or the festival. Nancy couldn’t help wondering why the woman had bothered to come to the barn dance at all—unless it was to cause trouble.

“And are you …?” Nancy asked.

“Rosalind Chaplin,” the woman replied with an annoyed sigh, as if Nancy should already know her.

“Take it from me,” Roz went on. “Vera Alexander is just a nosy newcomer who’s trying to make a big splash with all her plans for White Falls. The last thing this town needs is a stupid museum.” Roz leaned forward and pressed her face close to Nancy’s. “And you can bet I’ll do everything I can to make sure it doesn’t open.”

With that, Roz readjusted the poodle on her arm and stalked away.

Nancy frowned as Roz’s red tweed suit disappeared into the crowd. The woman had said almost exactly the same thing that the anonymous caller had told Vera.

Quickly filling two mugs with cider, Nancy rejoined Bess and George. “Hey, you guys,” she said, handing George her cider, “I just met our top suspect.”

“Roz Chaplin?” George scanned the crowded barn. “Where?”

“She’s wearing a red suit,” Nancy answered. The developer seemed to have been swallowed up by the crowd, but Nancy did see Vera. The musicians had taken a break, and Vera was talking to one of them near the refreshment area.

A few straws of hay wafted down from the hayloft above her, but Vera merely batted them away and continued her conversation.

Looking up, Nancy saw that the bales of hay in the loft above Vera were trembling. Suddenly one of them rocked wildly, tipping toward the edge of the platform and sending a shower of straw to the floor below.

The next thing Nancy knew, the huge bale was tumbling over the edge of the loft—heading straight toward Vera!

A Harmonica in a Haystack

“Vera! Look out!” Nancy shouted. She hurtled across the refreshment area, grabbed Vera by the waist, and dove with her to the side. Both of them hit the floor with a thud.

A split second later, the floor shook as the bale of hay crashed down exactly where Vera had been standing.

Nancy untangled herself from Vera and brushed some loose strands of prickly hay from her face. “Vera, are you okay?” she asked breathlessly.

The force of the fall had thrown Vera flat on her back, and her hair was a confused swirl covering her face. As Vera pushed the long strands back, Nancy could see a glimmer of fear in her dark eyes. “I th-think so,” Vera stammered. “How on earth did that happen?”

Nancy looked up at the loft again, but the hay now appeared quite still. “Someone must have pushed one of the bales,” she said angrily.

Nancy jumped to her feet and began pushing through the crowd that had gathered around them. Then she sprinted up the wooden stairway that led to the loft, pausing at the top to let her eyes adjust to the dimness.

Bales of hay were stacked three and four deep along the back and side walls of the loft, and loose straw littered the open center. Some of the bales were close to the edge of the loft, but Nancy was sure they couldn’t just fall over by themselves. On the other hand, she didn’t see anyone, or any spot where the culprit could hide.

As Nancy began sifting through the loose straw for clues, a sudden blast of cold air hit her back, making her shiver. She turned and peered into the shadows of the back wall. She could just make out the gleaming metal of a door latch and a sliver of star-studded sky.

Hurrying over to the spot, Nancy found a wooden door between some bales of hay. It was open a crack. She carefully peeked out through the opening. The top of a ladder was propped up to the loft door from outside, its rungs glistening in the moonlight.

“So that’s how the person got away,” she murmured aloud. Still, no one was on the ladder, or anywhere Nancy could see on the snowy ground below.

“Did you find anything?”

Nancy turned to see George at the top of the stairs. “The escape route, but not the attacker,” Nancy told her, pulling the door shut again.

As she walked toward Nancy, George scanned the dim hayloft.

“Hey, what’s this?” she asked as her foot hit a shiny metal object in the loose straw. She bent down and picked it up. “A harmonica! That’s funny. Here, take a look.”

“A harmonica? I wonder if …” Taking the small instrument from George, Nancy went over to the top of the stairway. Down below, the lively strains of music had started up again. “Remember that boy who was playing the harmonica,” Nancy said excitedly, looking down at the musicians’ platform. “He seemed really angry before, and now he’s gone.”

George looked at Nancy skeptically. “Do you really think a kid pushed that bale of hay?” she asked. “Why would he want to hurt Vera?”

“I don’t know,” Nancy admitted. Her eyes were still focused on the dance floor below, where another square dance was in progress. Vera, Bess, and Julie were sitting it out, talking quietly together.

Nancy’s gaze lit on a red tweed suit near the barn’s sliding door. “That’s weird,” Nancy said softly. “Hey, George. Look at Roz Chaplin.”

“What about her?” George asked, spotting Roz.

“Doesn’t she seem kind of nervous to you?” Nancy said. “She keeps looking over at Vera. And look at her dog.”

Roz had Fifi in her arms and was brushing frantically at the poodle’s plaid costume. Then, with a last look over her shoulder at Vera, Roz disappeared through the barn door.

George drew in her breath sharply. “Her dog’s covered with straw! Maybe Roz was the one who knocked over that bale. If you ask me, that’d make more sense than a kid being responsible. Maybe this harmonica isn’t even his.”

“Maybe,” Nancy replied, turning the small instrument over in her hand. “I know one thing for sure, though. I’m going to have to find out more about both of them.”

“So you really think Roz might be the one who’s after Vera?” Julie asked the next morning. She had arrived at Vera’s house just as Nancy, Bess, and George were finishing up the breakfast dishes. Now they were all helping Vera sift through the mess in the workroom.

“I don’t have any proof yet, but I wouldn’t be surprised if Roz is up to something,” Nancy answered. She brushed back her reddish blond hair with a dusty hand. “I also want to question that harmonica player I told you about, Vera.”

Nancy held up an extravagant hat made of maroon velvet, ribbons, and feathers. “Is this for the museum or the crafts auction?” she asked.

“Oh, that’s gorgeous,” Bess crowed. “They sure made things fancier in the old days.”

“Smaller, too,” George said dryly. She was peering doubtfully at a tiny satin lady’s shoe in her hand. “I might be able to squeeze my big toe in here, but that’s about all.” With a shrug, she asked, “Where should I put this, Vera?”

Vera chuckled as she pointed to the far end of the workroom, where a row of labeled cardboard cartons was arranged along the wall. “All of the clothes are for the museum,” she said. “You’ll find the boxes back there. The crafts, like quilts and boxes and anything made of wood or iron, are stored on this side of the room, near the door.”

Turning back to Nancy, Vera said, “As for the harmonica player, his name is Mike Shayne. I hired him a few months ago to run errands. He did a great job until about two weeks ago, and then …” Vera frowned, letting her voice trail off.

“He was stealing money from Vera, so she had to fire him,” Julie finished. The young woman sat down at the computer and began typing inventory items from a list on the desk.

Nancy raised her eyebrows. “Really?”

Vera nodded. “Every time I gave Mike ten or twenty dollars for an errand, he returned with only a fraction of the change I knew I should have gotten. When I confronted him about it, he admitted to stealing the money, but he wouldn’t explain why.” Vera sighed, plucking at the cotton of a quilt she was folding. “I would have lent him the money if he’d asked, but under the circumstances I felt I had to tell his aunt and uncle—”

“Not his parents?” Nancy interrupted.

Vera shook her head. “His mother and father died in a plane crash when Mike was a few years old. He’s lived with his aunt and uncle ever since.”

“I see,” Nancy said thoughtfully.

“If you want to talk to him,” Vera went on, “you might try Shayne’s General Store. Mike’s aunt and uncle own the place. School’s on vacation this week, and Mike helps out there in his free time.”

“What about Roz’s office?” Bess asked. “Where’s that?”

“You’ll need to drive there, I’m afraid,” Vera told the girls. “Why don’t you take my van? The maple boil isn’t until two, so I won’t need it until after lunch.”

Nancy smiled at her old neighbor. “Thanks, Vera.”

Vera placed some folded clothes inside a wooden captain’s chest and closed the top. “You’re sure you wouldn’t rather see some of the local sights?” she asked. “We don’t have much, but you might want to visit Esther Grey’s house.”

“The poet?” Bess asked eagerly. “We studied her work in tenth grade. I forgot she lived in White Falls.”

Vera nodded. “Her house is quite close to here.”

Nancy brushed the dust from her jeans and stood up. “I think for now we’d better concentrate on finding the person who stole that trunk yesterday,” she said.

“Not to mention whoever’s been threatening you, Vera,” George added. “And the person who pushed that bale of hay.” She turned to her cousin. “Sorry, Bess. Maybe we’ll go to Esther Grey’s house later.”

The girls were about to leave when Bess paused next to the computer table. “Oh, look,” she said, picking up an old leather volume with the initials ZC stamped on its cover in gold. “What a beautiful old book.”

“I’ll take that,” Julie said, taking the book from Bess. Then, seeing Bess’s look of surprise, she explained, “Sorry, I guess I get overprotective of all the stuff here. It’s funny. I never even look at any of these things—they’re just entries in the computer inventory to me. But until something’s logged on the computer, I feel very responsible for it.”

“Logging it in will only take a second,” Vera said. She crossed over to the computer desk and took the book from Julie. “Besides, I’ve already noted it on the list I gave you. I’m sure it won’t hurt for Bess to take a look at this.”

From Julie’s expression, Nancy guessed that she didn’t agree with Vera. But she didn’t say anything more as Vera handed the book to Bess.

“You might find it interesting,” Vera said. “It’s Zach Caulder’s diary.”

Bess’s eyes widened. “You mean the guy who was murdered?” Vera nodded. “It was donated by the town just recently. I haven’t even had a chance to read it yet, but I bet it’s fascinating.”

As Bess began flipping through the diary, George tugged on her arm. “Later, Bess. We’re on a case, remember?”

“Okay, okay,” Bess replied. She tucked Zach Caulder’s diary in her bag, then followed her friends out the workroom door. “Bye, Vera. Bye, Julie,” she called over her shoulder. “And thanks for lending me the diary.”

Following Vera’s directions, the girls drove down the curved, snow-lined road to Main Street, which ran along the river. Shayne’s General Store was a wide, low storefront between the post office and a farm equipment store. The girls stomped the snow from their boots, then went inside.

A bell jingled as they entered. A stern-faced woman at the check-out counter glanced up and said hello. Nancy saw that it was the same woman who had forced Mike to play the harmonica at the barn dance. She smiled and said hello to the woman as they passed.

Wide wooden shelves ran up and down the store in rows. They held everything from groceries to gardening tools to rain ponchos. An old-fashioned soda counter stretched along the wall to the right. The counter had a faded, red fake-marble top and aluminum stools with peeling red vinyl seats.

“There he is,” George said in a low voice, gesturing to the boy behind the soda counter. Nancy immediately recognized the curly-haired boy. He was bent over a comic book, his elbows propped on the counter.

“And look what’s behind him,” Bess added in an excited whisper. Nancy glanced at the shelf behind the counter, where a harmonica lay. “I wonder if that’s the same one he played last night,” she whispered back. “Let’s find out.”

As the girls sat down, the curly-haired boy looked up from his comic book. Up close, Nancy saw that he had big brown eyes and a round face. “Oh, hi,” he greeted them, standing up straight. “Can I get you something?”

Nancy and Bess ordered vanilla milk shakes, and George chose chocolate. As the blenders whirred, Nancy turned to Mike. “You’re a pretty good harmonica player,” she told him. “We heard you playing last night at the barn dance.”

A slight frown came over Mike’s round face. “My aunt made me go,” he grumbled. “But I knew that dance was going to be awful, just like the rest of the dumb crafts fair.” He shoved his hands into his jeans pockets. “I even lost my harmonica there. I had to buy a new one today.”

Nancy reached into her parka pocket and pulled out the harmonica she’d found in the hayloft. “Is this it?” she asked.

“Hey!” Mike shot Nancy a leery glance as he grabbed it from her. “Where’d you get that?”

“In the hayloft at the barn dance,” Nancy said.

Mike shook his head in disgust. “I can’t believe someone stole it from me and left it up there,” he said.

The boy sounded sincere, but Nancy couldn’t be sure he wasn’t just saying that to throw them off. She decided to try a different approach. “Mike, someone pushed a bale of hay at Vera Alexander last night. She could have been badly hurt if it had hit her.”

For a moment Mike just glared at Nancy. Then he said angrily, “It’s too bad it missed her. Vera’s ruining everything!”

Without another word, Mike took his comic book to the very end of the counter. He continued reading it there, studiously ignoring them.

Shooting a backward glance at her friends, Nancy picked up her milk shake and walked to Mike’s end of the counter. “You don’t seem to like Vera very much,” she said gently. “Why not?”

Mike’s brown eyes flashed with anger. “It’s none of your business,” he said. “And you should tell Vera to mind her business, too. She’d better stay away from Caulder Cutlery—if she knows what’s good for her!”

A New Twist

Nancy exchanged looks with Bess and George. Why would Mike care about Vera’s plans for Caulder Cutlery?

“What do you mean?” Nancy asked Mike. “Are you talking about Vera’s project to turn the factory into a museum?”

The boy gave Nancy another icy stare. Then he stormed to the back of the store, disappearing through a doorway that looked as if it led to a storeroom.

“Wow,” Bess said, stirring her milk shake with her straw. “Talk about touchy!”

Still gazing in the direction of the storeroom, Nancy murmured, “I wonder if—”

“I must apologize for my nephew’s behavior,” a tight, worried voice interrupted.

The girls turned to find the woman from the checkout counter standing next to them. She was twisting the hem of her grocer’s apron in her hands. “Mike has been such a trial to us lately. I’m afraid I don’t know quite what to do with him.”

“No harm done,” George said pleasantly. She finished the last of her milk shake and put the glass on the counter.

“You’re Mike’s aunt?” Nancy asked. The answer seemed obvious, but Nancy wanted to get the woman talking about him.

The woman nodded curtly. “I’m Grace Shayne. My husband and Mike’s father were brothers. I just don’t understand it,” she said, the worry spilling from her voice. “Up until recently, Mike has never been a problem. But during the last week or so …” She broke off with a sigh.

That was about the time Vera had started receiving the threatening phone calls, Nancy realized. “What has Mike been doing?” she asked.

“Oh, skipping school, avoiding his chores here at the store, disappearing at odd hours,” Mrs. Shayne replied. “And the boy refuses to give any explanations.” She shook her head critically. “He’s looking for trouble, if you ask me, the same way his grandfather did.”

As the woman spoke, she seemed to become more agitated. “Charlie Shayne was a bad apple if there ever was one,” Mrs. Shayne went on. “Maybe it was never proven, but everyone knows he’s the one who killed Zach Caulder.”

Nancy looked at her friends in surprise. She knew it would be impolite to pry, but she couldn’t resist asking Mrs. Shayne, “You mean the man who was murdered in the old knife factory?”

Mrs. Shayne covered her mouth with one hand. “Oh, my,” she said nervously. “I shouldn’t be talking this way. Charlie is my husband’s father, after all. It’s just that I get so mad thinking about the terrible thing he did.”

“Maybe he didn’t do it,” George suggested. “I mean, how could people be so sure Charlie killed Zach Caulder if the police couldn’t prove it?”

Mike’s aunt pressed her lips together in a tight line. “I wish I could believe that,” she said grimly. “But people saw Charlie leave the factory the night of the murder. And when he left town right after that, it was the same as admitting he was guilty.” She gave a bitter snort before adding, “Of course, he left the rest of the family here to live with the shame of what he did. I just hope he doesn’t ever come back.”

Nancy drummed her fingers on the faded red countertop. She couldn’t help feeling sorry for Mike’s aunt. But right now she had a case to solve. She was trying to turn the conversation back to Mike when the jingling of bells at the store’s entrance announced another customer.

“Oh, dear,” Grace Shayne said worriedly. “Here I’ve been rambling instead of keeping an eye on things. Excuse me, girls.” With that, she rushed back over to the checkout counter.

“What a story,” Bess said once she, Nancy, and George had paid for their milk shakes and were back out on Main Street.

“Mmm,” Nancy said. She sighed as she zipped up her parka. “It’s too bad we couldn’t get more of the story on Mike, though.”

“I know what you mean,” George said. “So why do you think he wants Vera to stay away from Caulder Cutlery?”

Nancy took the keys to Vera’s van from her jacket pocket. “Maybe he thinks the cutlery will remind everyone that his grandfather might be a murderer.”

“Maybe,” George said thoughtfully. “Anyway, I’m beginning to think you’re right about him pushing that hay down on Vera last night. Did you see how mad he got when you mentioned her name?”

George looked amused when she saw the faraway look in her cousin’s eyes. “Earth to Bess. Are you there?”

“Oh, I guess I was daydreaming,” Bess admitted, shaking herself. “I keep thinking about Zach Caulder. I mean, the whole story’s so amazing, and I even have his diary right here.” She tapped her bag, then looked sheepishly at her friends. “I can’t help wondering what the man was like. Would you guys, um, mind if I didn’t go with you to Roz Chaplin’s office?”

Nancy laughed. “Let me guess. You can’t wait a second longer to start reading that journal. Sure, Bess, we’ll meet you back at Vera’s for lunch.”

“There it is,” George said, pointing as Nancy pulled into the parking lot of a short strip of new-looking stores and offices on the outskirts of White Falls. A sign that read Chaplin Real Estate Development hung outside an office at the end of the strip. Nancy parked Vera’s minivan in front of it.

Getting out of the van, Nancy and George paused to look at the photographs of houses and commercial buildings that were taped to the office’s front window.

“No wonder Roz hates Vera’s museum project,” George commented. She pointed to a modern metal-and-glass condominium building. “Roz’s idea for White Falls is totally different from Vera’s, that’s for sure.”

Nancy nodded. “The question is, how far would Roz go to keep Vera’s plan from succeeding?”

The girls entered the office just as Roz strode purposefully out of a back office, followed by an eager young man with slicked-back blond hair. The man was wearing a gray suit and taking notes furiously on a large pad.

“And then I need you to check up on the crew at the Olmstead Street renovation,” Roz said over her shoulder. “Arnie told me the refrigeration is being installed today.”

The real estate developer frowned as she saw Nancy and George standing inside the door. “Oh, it’s you,” Roz said. She seemed anything but pleased to see them. “Nancy Drew, right?”

Nancy nodded. “And this is my friend, George Fayne. We’d like to talk to you for a moment, if you don’t mind.”

Roz waved her hand impatiently. “Can’t you see I’ve got a million things to take care of here? I couldn’t possibly—”

“We’ll be very quick,” Nancy promised.

Roz opened her mouth as if to object, but then she seemed to think better of it. “This way,” she said, showing Nancy and George into her inner office. She sat behind a desk with a smoked glass top and motioned for the girls to sit in the two leather and chrome chairs.

Glancing around the small room, Nancy didn’t see a trunk, but she didn’t really expect Roz to leave a stolen trunk where anyone could see it.

Nancy wasn’t sure what to say, so she decided to be direct. “I don’t know if you’re aware that Vera Alexander has been receiving threats to drop her plans to renovate the Caulder Cutlery factory into a museum,” Nancy began.

A satisfied smile rose to Roz’s lips. “It’s nice to know I’m not the only one who has the sense to oppose her plans,” she said.

The developer didn’t seem surprised by the news, but it was hard to tell for sure. Nancy leaned forward in her chair. “A wooden trunk of quilts for Sunday’s auction has been stolen,” she added.

“Not to mention that Vera was almost knocked over by that bale of hay last night at the dance,” George put in.

Nancy nodded, then turned back to Roz. “You wouldn’t happen to know anything about that, would you?”

Roz looked quickly from Nancy to George. “It was probably an accident,” she said smoothly, but Nancy noticed her fingers fidgeting nervously with some papers on her desk.

“I don’t have to resort to those kinds of tactics,” Roz went on. “My business is more of a success than any project of Vera’s will ever be. By modernizing old farm buildings and houses, I’m helping to bring new industry to White Falls.”

“You mean, by totally destroying beautiful old buildings,” Nancy said before she could stop herself.

Roz’s smile faded to a dark frown. “You’ve been spending too much time talking to Vera. She’s getting everyone all excited over that worthless museum project of hers.”

“But don’t you think White Falls’s history is worth preserving?” George asked. Nancy could tell her friend was fighting to keep her temper.

“My family has lived in this area since the seventeen hundreds,” Roz said haughtily. “Some of my relatives are world-famous. I’m as proud of my heritage as anyone.” She paused. “I just don’t see any use in harping on the ancient past. What we really need in White Falls are modern buildings and businesses for the future.” Just then the young man stuck his head in the doorway. “Ms. Chaplin, the furniture for the ski condos is here,” he said.

“It’s about time,” Roz said, getting quickly to her feet. “I’d better see to the unloading myself.” Nancy thought the woman seemed relieved for an excuse to end their conversation.

“Do you mind if we tag along?” Nancy asked.

Roz shot her an annoyed look. “I suppose it won’t do any harm,” she said.

Nancy and George followed the developer down a hallway and through a door that led to a garage. A big truck had pulled up to the garage’s outside door, and two men were unloading black couches and chairs wrapped in protective plastic.

“No, not there!” Roz called. Her heels clicked on the cement floor as she hurried over to one of the moving men and tapped him on the shoulder. “Over there,” she ordered, pointing to a clear section along the garage wall. “Can’t you people ever get anything right?”

“What a dragon!” George whispered to Nancy. “The way she’s hounding those guys, I wouldn’t blame them if they decided to drop that stuff right on her.”

Stifling a laugh, Nancy glanced around the garage. Sleek, modern furniture, unopened packing crates, and rolls of carpeting and fabric were scattered in no special order. Seeing that Roz was still badgering the furniture movers, Nancy began strolling around the garage, keeping an eye out for a black lacquered trunk.

She had just taken a few steps when a growling noise behind her made Nancy pause. Instinctively she tensed. But when she turned around, she saw that it was only Roz’s little dog, Fifi. The white poodle was half-hidden behind a wooden crate. Its teeth were clamped around one end of what looked like a blanket that the dog was pulling from side to side, as if she were doing battle with it.

“Oh, isn’t she a cute little thing,” George said softly.

“Fifi, the mighty warrior,” Nancy joked. A moment later, she drew in her breath sharply. Fifi had dragged the blanket farther out, revealing a multicolored star pattern. “George! Look, it’s a quilt!”

George stared at Nancy as if she had lost her mind. “Yeah. So?”

“So, what’s an old patchwork quilt doing with all this modern stuff?” Nancy asked excitedly. “And look where Fifi’s pulling the quilt from! ”

George’s brown eyes widened with understanding as she saw what Nancy was pointing to. The trunk was mostly hidden behind the wooden crates, but one black lacquered corner was visible. George whistled softly. “Vera said the stolen trunk was a black lacquered one with quilts inside,” she said.

Nancy nodded triumphantly. “I think we’ve found our thief!”

Found—and Lost

“Let’s take a look,” Nancy told George in a low voice. “If we find yellow paint on that trunk, we’ll know for sure that it’s the one that was stolen from Vera.”

“You mean the paint would show from where the trunk nicked the new paint in the doorway?” George asked.

Nancy nodded and took a step toward the trunk. In the next instant, however, she was jostled to the side as Roz swept past her. “Fifi! Let go of that,” Roz scolded, scooping up the little dog and prying the quilt from Fifi’s mouth. Then she grimaced, holding a corner of cloth between her thumb and forefinger as if it were some sort of slimy rag. “What is this old thing doing here?” she asked disdainfully.

Roz’s gaze fell on the black trunk, and Nancy saw her face freeze for a second. Then, just as quickly, Roz turned toward Nancy and George and began hustling them away from the trunk.

“It’s a lovely quilt, Roz,” Nancy commented, trying to resist the woman’s insistent pushing. “I’d love to take a closer look at it.” She peered back over her shoulder at the trunk, trying to see if there were any signs of yellow paint.

But Roz ushered her and George firmly back into the office. “I’m sorry, girls, but I have to get back to work now,” she said. Nancy thought she detected a slight note of nervousness in the developer’s voice. “Perhaps another time.”

Before Nancy and George knew what was happening, Roz had led them to the front door of the office and ushered them outside. “Good day, ladies,” she said, closing the door behind them. Nancy watched through the window as Roz stormed through the doorway to her private office and disappeared inside.

“We were so close,” George said, stamping her foot in frustration. “I bet anything that was the trunk from Vera’s.”

Nancy hurried to the side of the real estate office in time to see Roz’s assistant close the garage door. Apparently the delivery men had just finished unloading the furniture. They were climbing back into the front of their truck and starting the engine.

Nancy let out a discouraged sigh. She and George would have to wait for another time to get a closer look at the trunk.

“There’s something I don’t understand,” Nancy said, going back to George. “Roz seemed as surprised as we were when she saw the trunk. I mean, if she knew about it, why would she let us go out to the garage in the first place?”

George shrugged. “Maybe she figured it was hidden well enough behind those crates,” she suggested. “If Fifi hadn’t drawn our attention to it, we probably wouldn’t have seen the trunk. I bet Roz was just pretending to act surprised to throw us off.”

“I guess you’re right,” Nancy said, pulling the keys to Vera’s van from her purse. “Anyway, there’s nothing more we can do here now. We might as well head back to Vera’s.”

“Bess, hurry up!” George called. “We don’t want to be late for the maple boil.”

“Especially since I promised Vera we’d be on the lookout for any trouble,” Nancy added. “We won’t be able to spot much of anything if we’re not even there.”

The two girls were waiting in the front hall of Vera’s house, wearing jeans, scarves, gloves, and heavy sweaters. Right after lunch, Vera and Julie had driven over to the farm where the demonstration would take place. Vera had left Nancy directions to the maple farm, saying that it would be a pleasant walk.

Nancy could hear doors and drawers banging upstairs in their room. Soon Bess raced down the stairs, pulling on her parka, hat, and gloves as she went.

“Sorry,” she said breathlessly. “I got so caught up with my reading that I forgot about making maple syrup this afternoon.”

George shot her cousin a look of total disbelief. “You forgot about tasting one of the yummiest things in the world?”

“I didn’t think any book could be that good,” Nancy teased as the girls left the house, locking the door behind them.

“Me neither, but I guess I was wrong,” Bess said. “You guys should get a look at Zach Caulder’s diary. You wouldn’t believe how juicy it’s getting. I mean, at first it was kind of boring—you know, mostly just a log of the factory’s expenses, how much cutlery was produced every day, stuff like that. One thing comes through loud and clear, though. Old Zach was very cheap. He wrote himself tons of reminders to watch over his foreman and the workers to make sure they weren’t stealing from him.”

“Maybe he had a good reason to be careful,” Nancy said. “After all, he was murdered.”

“Ooh, don’t remind me,” Bess said with a shiver. “Anyway,” she went on excitedly, “now Zach is starting to write more personal stuff. He’s being wooed by a mystery woman. Someone left flowers in his car at the factory last night, along with an anonymous love note.”

George rolled her eyes. “Bess, I hate to disappoint you, but Zach Caulder’s been dead for over fifty years. You’re talking about this guy as if he’s still alive.”

Bess smiled sheepishly at her friends. “I guess reading his diary makes me feel as if he is.” Then she shook her head. “If Zach were alive, though, I don’t think I’d want to know him. He sounds like a real miser.”

The girls crossed over Main Street, and their boots crunched on the snow as they started on the pedestrian walkway of the bridge over the Deerfield River. About halfway across, Bess paused to lean against the safety railing. Her eyes were on the stone factory perched on the opposite bank, above the falls.

“I’m so glad Vera’s making Caulder Cutlery into a museum,” she said.

“It is a beautiful building,” Nancy agreed. The ivy over the old factory was so thick, it almost completely covered the structure, but Nancy could make out indentations where sunlight glinted on glass windows. There were two rows of four windows each. For a moment she enjoyed the view, letting her gaze wander over the woods that hugged the cliff on either side of the factory. Then her eyes rested on the bright white of a snowy clearing, and the colorful jackets and coats of the people gathered there. “Come on, you guys,” Nancy said.

They hurried the rest of the way across the bridge and entered a snowy gravel drive marked Owens Maple Farm. Circling around a wooden farmhouse, the girls found themselves in the clearing Nancy had seen from the bridge. The day was fairly warm, but several inches of snow still covered the ground and the branches of the surrounding trees.

The participants were spread out in different groups. Some were collecting sap into wooden barrels on sleighs. Others were pouring the sap into a huge cast-iron pot that hung over a low fire. A handful of men and women wearing green Owens Maple aprons over their sweaters seemed to be directing the various demonstrations.

At one side of the clearing, a raised trough had been filled with snow. Vera was helping a group of children pour the hot syrup into shapes that hardened into maple sugar on the snow. She had a scrapbook of old photos and engravings of New England “sugaring off” gatherings, which she was showing to the children.

“There you are,” Vera said, smiling as the girls walked over to her. “Julie just went back to the house to do some more computer work. She had strict orders to send you three up here right away. I didn’t want you missing one of the best parts of the whole crafts fair.”

“Mmmm,” Bess said, sniffing the sweet, maplescented air. “I hope someone’s making pancakes to put all this syrup on.”

Vera laughed and pointed back toward the farmhouse. “As a matter of fact, Trisha Owens is whipping up a huge batch right now.” As Bess and George joined a group collecting sap from the wooden taps in the sugar maple trees, Nancy scanned the area.

Sunlight glinted off the snowy clearing, and Nancy shaded her eyes with her gloved hands to see better. So far, so good, she thought as she gazed at the different groups of people. The maple boil seemed to be going smoothly.

Suddenly Nancy tensed. Out of the corner of her eye she spotted a flash of blue and red at the edge of the clearing. Looking more closely, she recognized Mike Shayne’s curly, dark hair above his blue jacket and red high-top sneakers. He was circling the edge of the clearing, looking furtively at Vera every couple of seconds. Even from fifty feet away, Nancy could see the angry glint in his eyes.

What’s he up to? she wondered, slipping quietly across the clearing toward him.

A moment later Mike’s eyes widened as they focused on Nancy. The boy broke into a run and tore off into the woods, disappearing behind a thick clump of evergreens.

In a flash, Nancy was after him. Snowy branches slapped at her face as she followed Mike’s footsteps through the dense, dim woods. She couldn’t see him, but the sounds of branches snap- ping up ahead told her she wasn’t far behind.

After about twenty yards, Nancy saw that the boy’s footprints had merged with other prints in what looked like a small path. Either Mike or someone else had been on it recently. Soon the path opened out into a clearing. Nancy paused to get her bearings, her chest heaving from running.

In the center of the clearing, an ivy-covered stone building rose two stories high. The building was perched right at the edge of the high riverbank. It was the Caulder Cutlery factory, Nancy realized.

Mike’s footprints didn’t lead to the factory’s wooden double doors, as she would have expected. Instead, they pointed in the opposite direction, around the side of the building. As Nancy began to follow the prints, she heard a rustling noise, then the squeaking of hinges.

Picking up her pace, Nancy circled to the side of the factory—and stopped short. There, about halfway along the factory wall, the footprints abruptly ended.

Puzzled, Nancy gazed up at the factory’s outside wall. The smooth surface of ivy-covered stone didn’t seem to be broken by any window or door. It was as if Mike had disappeared into thin air.

Think, Nancy, she told herself, frowning. There had to be a way in. Stepping closer to the wall, she brushed her gloved hands through the thick tendrils of ivy, working her way over the entire area next to the last set of footprints. About four feet above the ground, her hand caught on something metallic. Pushing the ivy aside, Nancy found a small window set into the stone, its glass thick with dust and grime.

Nancy’s heartbeat quickened as she pushed in the window. It gave way with a creak of its rusty hinges. A moment later, she climbed up and through the window, dropping to a wooden floor. The sound echoed in the cavernous space.

Peering around, Nancy saw that she was standing in a large room that must have been the factory’s main work area. It was now empty of any equipment or workbenches, though some rusty metal bins and loose debris had been swept into one corner.

Nancy didn’t hear any movement. Some light filtered through the windows, though, and she was able to spot wet footprints leading across the floor. A rickety-looking wooden stairway at the far end of the room led up to a wide balcony that jutted out over the main floor. A second stairway led downward from the main level, into a basement.

Had Mike gone up or down? The wet footprints dried out before the stairs, so it was impossible to tell. Nancy glanced up toward the three doorways off the upper balcony, but she decided it would be better not to risk the rickety stairs unless she had to.

Crossing over to the basement stairwell, Nancy gingerly tested the top step with her foot. It creaked but seemed solid enough. Feeling along the wall with her hands, Nancy made her way carefully down the black, shadowy stairwell. The stairs turned, finally opening out into what had once been a storage room.

The three windows in the lower level provided some light. Nancy quickly saw that Mike wasn’t there. Like the main level above, the room had been emptied of whatever it had once held. Only the bare shelves that lined the four walls remained.